As the Regional Community Partner for AIDS 2016, ARASA is committed to assisting civil society and community members to attend the conference, host activities or workshops and facilitate presentations. Although ARASA has no funding for registration, accommodation or travel costs, a dedicated staff member will be able to assist with all registration and abstract, scholarship, Global Village and Youth Programme applications.

The 2016 International AIDS Conference, can we help you?

Plenary Line Up

See the plenary line up for AIDS 2016 here.

Letter to President Obama: Don’t stall HIV/AIDS research funding

Organizations from across the US—nearly 140 of them—penned a letter to President Obama urging that the NIH budget (responsible for 68 percent of the global public sector HIV prevention research budget) include the US $100 million increase for HIV/AIDS research for FY2016 promised by the President in March of 2015. Noting that now is a time to prioritize, not cut HIV/AIDS research, the letter highlights the potential for research advances to help “end the scourge of HIV/AIDS”, a priority the President himself called out in his recent State of the Union speech.

This letter and a companion letter, signed by over 500 researchers supporting HIV research funding, are available to download here.

Contribute to the AIDS 2016 conference programme!

Be part of the world’s premier gathering where science, leadership and community meet for advancing all facets of collective efforts to treat and prevent HIV. Submit an abstract and share your research. Submit a workshop that will promote knowledge transfer, skills development and collaborative learning. Submit an activity for the Global Village and Youth Programme. Programme submissions are open until 4 February 2016.

Call for contributions

The United Nations Secretary-General’s High-Level Panel on Access to Medicines is calling for contributions by interested stakeholders that address the misalignment between the rights of inventors, international human rights law, trade rules and public health where it impedes the innovation of and access to health technologies.In particular the High-Level Panel will consider contributions that promote research, development, innovation and increase access to medicines, vaccines, diagnostics and related health technologies to improve the health and wellbeing of all, as envisaged by Sustainable Development Goal 3, and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development more broadly.

Sweet 16: HIV Advocates to Watch in 2016

AVAC joins My Fabulous Disease Blogger, Mark King, in his recognition and praise for the promise of 16 diverse HIV leaders. His list includes Cassie Warren and Nick Feustal who—in addition to being leaders in the great work described in Mark’s piece—are also members of AVAC’s PxROAR program.

As Mark puts it, “They come from nearly every corner of the world. They are engaged in local communities and on the international scene. They include mothers, artists, a fugitive, a performer, and a drug smuggler. They are speaking out, acting up, and in some cases risking their personal safety and liberty.”

We are grateful to have Cassie and Nick as part of our partner network and look forward to working with them and all of you in what should be an exciting 2016. Cheers!

Read the full piece here.

Develop, Demonstrate, Deliver: Model shows AIDS vaccine is essential to conclusively end epidemic

ARV-based HIV prevention implementation is on a roll, with WHO recommending daily oral PrEP as an option for all people at substantial risk of HIV acquisition—and also calling for immediate offer of treatment to all people living with HIV. TDF/FTC (brand-name Truvada) is now approved for HIV prevention as PrEP in France, Kenya, South Africa and the United States—with more countries sure to follow in 2016.

These advances may lead people to ask whether the world still needs an AIDS vaccine as part of the strategy for ending the epidemic? And will a vaccine be needed in five or ten years time—the likely timeframe for results on today’s leading candidates to end the epidemic? For prevention advocates who don’t want to settle for a limited set of options, and who understand the potential revolutionary impact of a vaccine, a new modeling analysis, published this month in the open-access journal PLoS ONE, provides some clear answers to this question.

The paper, Exploring the Potential Health Impact and Cost-Effectiveness of AIDS Vaccine within a Comprehensive HIV/AIDS Response in Low- and Middle-Income Countries, was authored by IAVI, Avenir Health and AVAC, with financial support from USAID.

It looks at the potential impact of an effective AIDS vaccine in the context of expanded coverage of early treatment, PrEP and other existing strategies reflected in the UNAIDS Investment Framework Enhanced (IFE). The IFE, published in 2014, assumed scale-up of ART according to WHO 2013 guidelines along with VMMC and the potential introduction of PrEP, and an AIDS vaccine. [Note: the 2013 WHO guidelines indicated treatment for individuals with a CD4 count of 500 or less; the updated guidelines released in 2015 indicate offering treatment to all HIV-positive individuals, regardless of CD4 count.]

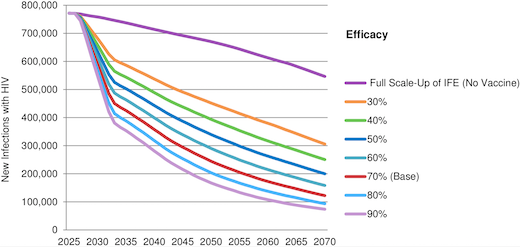

The paper reflects that if UNAIDS IFE goals were fully achieved, new annual HIV infections in LMICs would decline

from 2.0 million in 2014 to 550,000 in 2070. A 70 percent efficacious vaccine introduced in 2027 with three doses, strong uptake and five years of protection would reduce annual new infections by 44 percent over the first decade, by 65 percent the first 25 years and by 78 percent to 122,000 in 2070. Vaccine impact would be much greater if the assumptions in UNAIDS IFE were not fully achieved. An AIDS vaccine would be cost-effective within a wide range of scenarios.

This paper suggests that even a modestly effective vaccine would reduce infections significantly and be cost-effective, even as other interventions are broadly implemented. This confirms what AVAC and others have often said before: no single option will or can end the epidemic.

When PrEP Educators Don’t Like PrEP: Minister Rob Newells’ message to naysayers

What do you do when the people responsible for implementing PrEP education programs don’t trust the science? What if the outreach workers and HIV test counselors believe they’re required to “push” PrEP at the expense of behavioral interventions that have been the focus of prevention programs for years? These are people in prime positions to provide PrEP education to key populations, but suggesting that otherwise healthy clients start a daily medication for prevention is a tough pill for some front-line staff to swallow.

I am a black MSM. I serve at a community-based organization where a large percentage of both the clients and employees are black MSM. One of the known barriers to PrEP implementation among black MSM is medical mistrust. Those barriers don’t just exist among clients; they also exist among members of the HIV workforce tasked with increasing PrEP awareness in their communities. If members of the HIV workforce don’t trust the medical establishment or clinical research or pharmaceutical companies or government agencies, how do we expect them to provide unbiased information about PrEP to the people who need it most?

With all of the good work HIV prevention research advocates have done educating the public about PrEP, there has been more than enough misinformation disseminated about PrEP to create and encourage lingering doubt in the minds of those who are already mistrustful of the medicalization of HIV and the perceived influence of pharmaceutical companies on the HIV prevention agenda. After the 2015 National HIV Prevention Conference in Atlanta, I listened to staff members who had attended as they reported back to staff that stayed behind:

- “There are lots of things we still don’t know.” (Never mind that we know HIV incidence in our Black MSM community is an overall 32 percent, surpassing rates in many populations in sub-Saharan Africa.)

- “We need more information.” (Never mind clinical trials and real-world evidence showing that PrEP is safe and effective and therefore FDA-approved and WHO-recommended.)

- “There are still questions about the long-term effects of the drug.” (Never mind that we have more than a decade of experience of Truvada in people who are HIV positive.)

- “People who take PrEP stop using condoms, and STI rates are increasing.” (Never mind the fact that STI rates started increasing before most people had even heard of PrEP. Furthermore, CDC PrEP protocol recommends STI screening, and treatment if necessary, every three months.)

So what do we do when the people responsible for implementing PrEP education programs don’t trust the science?

If I could talk to all of the PrEP-hater educators, I’d tell them that I wish Truvada had been available for HIV prevention when I was treated for syphilis in 2003. It took several months to get to a syphilis diagnosis because I was treated for a skin rash and gout and had a sigmoidoscopy (an invasive large-intestine probe) before the doctor even ordered an HIV test. (This was before rapid testing was widely available, so I had to think about all of my risky behaviors for a couple of weeks before I got the call that the test was negative.) It was the only time I had ever been worried about HIV infection. It took a while longer before the doctor ordered an STI screening, discovered the syphilis, and ordered the appropriate treatment.

After dodging that bullet, I would have jumped at the chance to protect myself from HIV infection by taking a pill every day. I was in my early thirties; I was a personal fitness trainer in Washington, DC with a good day job; and I had a fairly active sex life. Sometimes I used condoms. Sometimes I didn’t. I had never had any concerns before, but that syphilis scared the hell out of me. It didn’t scare me after I found out what it was because syphilis is totally treatable. It scared me when I thought that I might have been infected with HIV. (It didn’t, however, scare me enough to make me increase my condom use to 100 percent consistently and correctly.) If a pill a day could take the worry of HIV infection from me, I would have been all for it. I wouldn’t have been concerned about long-term side effects or toxicities. I was concerned about living.

If Truvada had been available as PrEP when I tested positive for syphilis in 2003, I probably wouldn’t have tested positive for HIV in 2005. The silver lining is that PrEP is available now. There are black MSM now – who like me then – would jump at the chance to protect themselves from HIV infection by taking one pill every day during their season of risk if they could have accurate, unbiased information about PrEP.

To all of the people responsible for implementing and educating communities about PrEP who don’t like PrEP, I say, “It’s not about you.” Your questions have been asked and answered. PrEP works (and is safe and effective) when it is taken according to the prescribing guidelines. Don’t let your personal or professional biases and misinformation become a barrier to key populations like black MSM accessing an HIV prevention option that might be right for them. PrEP is not appropriate for everybody, but everybody needs to know about PrEP. Get out of the way.

Rob Newells is the newly appointed Executive Director of AIDS Project of the East Bay; he is minister and founder of the the HIV program at Imani Community Church in Oakland and is a PxROAR member since 2012.

Activist Asserts African LGBTQ Alliances Overseas are Key to Protective Policy and HIV Services

The December 20 New York Times article, “US Support of Gay Rights in Africa May Have Done More Harm Than Good” argued that the new level of LGBTQ harassment in Africa is an unintended result of increased American support for protective policies and HIV services. In other words, so-called US cultural imperialism is a primary cause of homophobia, specifically in Nigeria, but also on the continent at large. The article has prompted many responses from African LGBTQ activists. Paul Semugoma, of Uganda, is one of the many voices arguing against the Times’ depiction of US funding as a liability rather than a lifeline.

I would disagree with the premise of the article.

I have heard similar arguments a lot, being Ugandan—the attendant argument that our fiercely loud fight against the Anti-Homosexuality Act in 2014 in Uganda resulted in the backlash on the rest of the continent. In my experience, and very respectfully, that is all bullshit. Because it is counter to the real history.

In Uganda, the President [Museveni] was a darling of the US presidents from Clinton through Bush. During the eight years of Bush, that is when the country was really opened up to the waves of evangelization from Americans. Those are historical facts. Ugandan Pastor Martin Ssempa—known for his feverish portrayal of gay men as those who ‘eat da poo poo’—was very vocal about the ‘right way’ to fight HIV: Abstinence, Being faithful. He was actually in the US Congress to highlight Uganda’s AB policy, back when Uganda was the AB ambassador of the world.

What was not really known to the rest of the world was that back home Pastor Ssempa was fiercely fighting an invisible foe—homosexuality. But, there was a crucial thing missing. There were no visible homosexuals in the country. He was shadow punching, very openly, very strongly, but fighting an invisible foe that only he saw as a clear and present danger. I know. I was living in the country. His ignorant utterings were felt by all of us. But we were completely invisible . . . that is, until there came a time when we decided that the risks of hurting our invisible, closeted selves were hurting us more than helping us. That was in 2007.

We held a press conference. I was there. And I did support the move. Because it was simple survival. We couldn’t become more demonized than we already were. The Uganda AIDS Commission was regularly pointing out that ‘there were no homosexuals’ visible. There was no need for our HIV prevention efforts.

After the press conference came the backlash. Ssempa organized protests and campaigns. He was very happy to go ahead and shout even louder. He had a visible foe then and continued to demonize us as much as he could.

To say that we as gay Ugandans were ‘responsible’ was to credit us with the supernatural powers that he was accusing us of. We were few, disorganized, poor, with actually no funding at all. Ssempa and company were rolling in US dollars from the abstinence and be faithful campaigns. They had political, social and financial support. We couldn’t even go on the airwaves. They did.

We didn’t organize Scott Lively’s visit to Uganda and the anti-gay seminar in 2009, widely believed to have paved the way for the ‘kill the gays’ bill.

Of course, when the Anti-Homosexuality Bill came into the country, we reached out, because we were drowning. And we did grasp at the straws that were then available to us. As our country-people debated putting us to death for the grave crimes of ‘aggravated homosexuality’, we embraced the help of foreigners who were like us, who could understand the horror of being the subject of moral murder and disdain.

Yes, we were lucky. At the same time there had been a sea change in the US—a traditionally ardent supplier of missionaries. With Obama as president, the LGBTQI movement was flexing political muscle. And we took advantage of it. Even in Europe.

No, I personally will not blame the gay men and women in the US who took on the fight against HIV. Because it was their lives at stake. They might have found a calling and reason to live through the AIDS scourge of the 80s, but they were simply surviving.

I will not blame those gay people working in HIV understanding that there was an issue with the ‘AB’ approaches. I will not blame them for making common cause with us. I will not blame them for being great allies and showing us the straws that were available. I know that the Anti-Homosexuality Bill’s death penalty provisions were defeated in the US, not in Uganda. I was there. I understood the dynamics. I knew we were powerless. And I knew where the leverage was, for my government.

Of course, there was apt to be backlash. Fair enough. And, of course, it has led us in ways and directions we had never thought possible.

But, in 2007, we had no HIV programme. But just last week, Sexual Minorities Uganda was celebrating the Equality Awards, celebrating a three-year partnership with the SHARP HIV/AIDS Alliance delivering an HIV programme to LGBTQIs in Uganda.

For one to tell me that our fight, the alliance with our allies overseas has done more harm than good is not to remember what was there, on the ground. I was there. I have been involved. No, I would rather that Ugandans who are gay know that HIV is spread through sex, than for them to assume that they are free of HIV because they have sex with men, and not with women. That time was then—we didn’t even begin to understand how much it was hurting us. But we know it did hurt us.

I must affirm that these are my thoughts. My strongly held opinions. But I am sure history supports me here.

Paul Semugoma is a Ugandan Physician and LGBTQI activist living in South Africa.