July 21, 2017

Last year at the Durban AIDS Conference, many of us donned big round stickers that said “Code Red” for HIV prevention. If you’ve got yours, perhaps on a conference bag or t-shirt, you’ve got the main message we’d like to convey regarding the new UNAIDS report on the state of the HIV epidemic.

One year later, we’re in a “code red” situation—with as much cause for alarm as celebration in the UNAIDS report on the global HIV epidemic released this week.

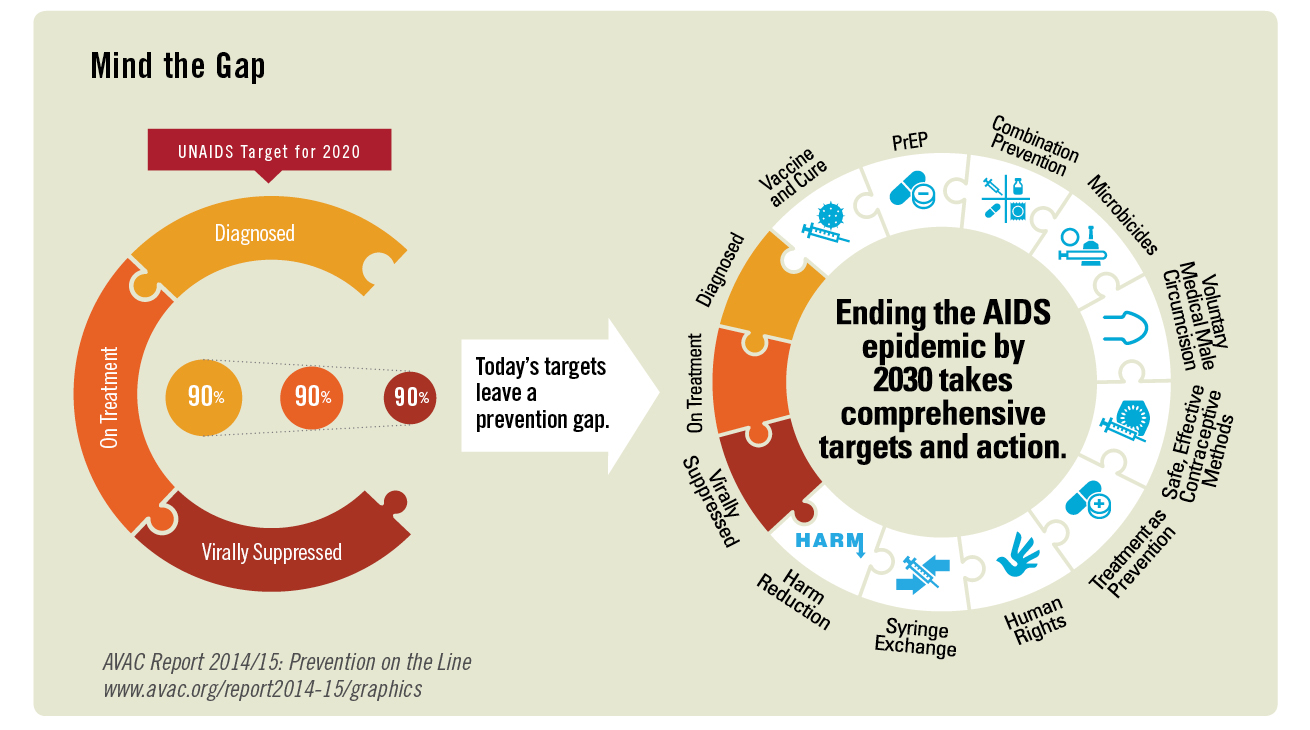

First, the good news: based on higher-quality data, UNAIDS has revised its 2016 estimates for rates of new HIV diagnoses in sub-Saharan Africa. This is great news, as is the overall progress reported towards achieving the 90-90-90 targets, which aim for 90 percent of people living with HIV knowing their status, 90 percent of those people linked to ART, and 90 percent of those individuals on ART achieving virologic suppression. These are essential targets for a rights-based response and sustainable end to the epidemic. This progress must be sustained and accelerated, picking up lessons from innovative, comprehensive service-delivery models like the SEARCH study, highlighted in the report.

Now, the reasons for the red alert. Rhetorically, UNAIDS has abandoned its comprehensive “Fast Track” framework in favor of exclusive emphasis on the 90-90-90 targets. These treatment targets are not enough. UNAIDS is a global thought leader and advocacy partner. Its messages matter. The message in this report—that 90-90-90 targets are the global HIV response—puts the field on the slow track.

The UNAIDS report is misleading in its top-line messaging. It credits a global decline in incidence to “acceleration of HIV testing and treatment—within a comprehensive approach that includes condoms, voluntary medical male circumcision, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), and efforts to protect human rights and establish an enabling environment for service delivery”. Yet globally, condom procurement and distribution numbers are dipping (the report gives information on condom usage, but not overall supplies or funding for programming); PrEP access is highly limited; annual VMMC numbers are not on track to reach the UNAIDS Fast Track target of 27 million by 2020 (noted nearly 100 pages into the report); and the human rights of those most at risk are tenuous at best.

The good news is that people living with HIV are accessing treatment, living healthy lives with dignity and that rates of AIDS deaths and new diagnoses are dropping. The bad news is that UNAIDS is providing a misleading picture of the state of all other primary prevention globally. Imagine what the world would look like if the Fast Track targets for VMMC, PrEP and human rights were actually being met.

Bringing epidemic levels of new HIV diagnoses and AIDS deaths to a conclusive, sustainable end depends on seeing the details, not just the big picture. In many sub-Saharan African countries there are twice as many young people as there were at the beginning of the epidemic. The fact that the number of new HIV diagnoses is remaining constant—and even dropping in some age groups, in spite of a growing population, is testament to effective programming.

But, as the report finally acknowledges more than 20 pages in, the world is not on track for reaching key goals in the reduction of new HIV diagnoses. In 2016, new HIV diagnoses among 15- to 24-year-old young women were 44 percent higher than men in the same age group. Global demographics are clear: the total population of young people will continue to rise, as will the percentage of those who are at risk of or diagnosed with HIV.

Current HIV prevention isn’t adequate to prevent new epidemics among the young people—particularly adolescent girls and young women—in this sub-Saharan African “youth wave”. Nor is it adequate for the alarming and unconscionable rise in new diagnoses in east and central Asia, where grossly inadequate harm reduction, TB treatment and human rights frameworks for addressing the epidemic are driving explosive epidemics.

Perhaps the best news is that HIV prevention advocates and activists know what needs to be done and will not give up fighting for it, using the scant references in the UNAIDS report to bolster strong arguments for a truly comprehensive response that includes:

- Adequate funding and smart programming leading to reliable achievement of ambitious targets (appropriate to the intervention) for VMMC, PrEP and condom promotion.

- Development and use of prevention cascades and continuums that allow countries to track the quality and impact of primary prevention and harm reduction programs with as much accuracy as their treatment programs.

- An all-hands-on-deck approach to meeting the prevention needs of the young people of sub-Saharan Africa, particularly girls and young women—as well as their male partners.

- Investment in and recognition of the need for continued research for new prevention options, including the dapivirine vaginal ring, next-generation PrEP products and a vaccine.

Above all, we need leadership. If that isn’t forthcoming from UNAIDS, we know where it can be found: in the vibrant, energetic and unstoppable HIV prevention movement. We’re on alert and in action! We’ll be bringing these messages to the fore at next week’s IAS 2017 conference in Paris—a key gathering for framing the global conversation; we’ll be working in small groups to develop specific strategies at country and community levels; and we’ll be convening via webinars, in-person gatherings and social media to provide the messages and momentum needed now.

Stay tuned, and join us. Every voice matters, now more than ever.