December 2, 2021

By Alice Kayongo, public health and human rights advocate, and senior policy advisor for WACI Health.

For over a decade, advocates for HIV prevention research have called for stronger political will and global solidarity towards a preventive vaccine and other prevention tools for HIV. COVID-19 has demonstrated how political will can help accelerate scientific breakthroughs. The COVID-19 vaccine is a case in point: science, political will and global solidarity came together to find a tool that has helped protect millions, and could protect billions if inequitable access issues are addressed.

As advocates call for action, it’s clear that greater domestic investment in health research and development (R&D) will be critical for improving health, equity and development. However, despite a disproportionately high burden of disease, Africa still lags in health R&D to address the region’s health challenges. We attribute this in large part to inadequate funding among other factors.

A recent publication, ‘Situation analysis report on the mobilization of resources for health research and development’, commissioned by Africa Free of New HIV Infections (AfNHi), WACI Health and Coalition to Accelerate & Support Prevention Research (CASPR), examines the financing problem of health R&D in Africa. It reports on progress but finds efforts have fallen gravely short of the target, with serious implications. This report comes at an opportune time, as COVID-19 puts a spotlight on the importance of health R&D and the need for greater domestic leadership and international commitment.

Accounting for over 15 percent of the world’s population, the continent bears 25 percent of the burden of disease at the global level, produces only 2 percent of the world’s research and only accounts for 1.3 percent of publications on global health. As explored in the report, regional commitments have been made to increase government spending on health R&D. For instance, the 2008 Bamako declaration calls on African governments to allocate at least 2 percent of budgets of ministries of health to research. Similarly, the 2008 Algiers Declaration calls on African governments to invest at least 2 percent of their national health expenditures and at least 5 percent of their external aid in projects and programs that build capacity and advance health research. However, despite such commitments, such investment remains gravely low in Africa.

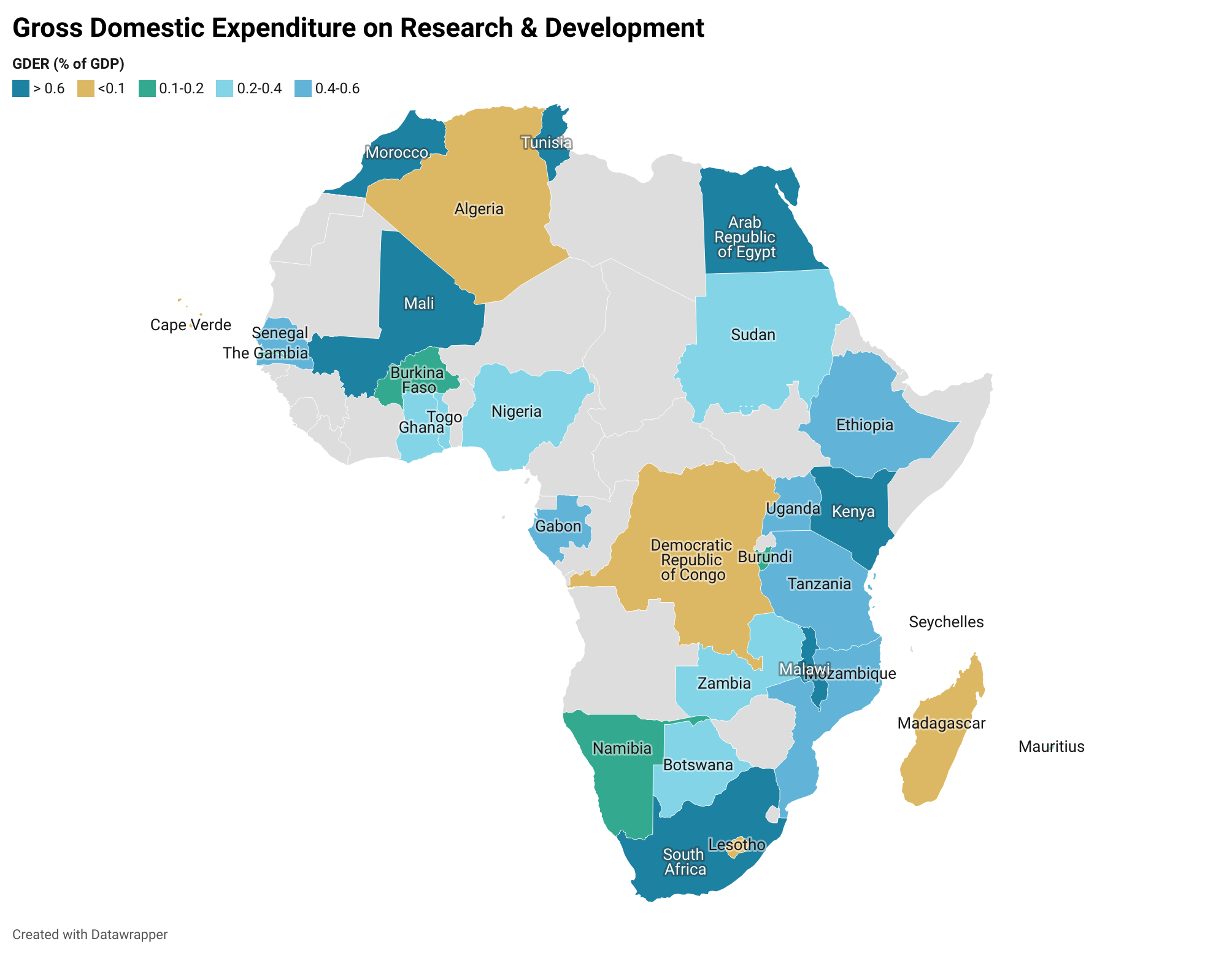

Source: Simpkins (2019); Analysis by AfNHi Consultant

Based on the map above, domestic funding is inadequate for sustained and impactful research in health as most governments are investing less than 2 percent of their GDP, yet several health problems demand more investigation, arising from specific conditions, such as HIV, Malaria, challenges to maternal health, that are so widespread that they undermine public health at large.

Financing for health, especially R&D, relies heavily on foreign aid. This presents opportunities and challenges. Foreign aid brings skills, technology transfer, infrastructure for research and other resources. But the challenges are important to consider. Foreign aid can put funder research priorities ahead of host country priorities. Foreign aid can also be tied to a lack of local ownership, exploitative research partnerships, focus on publications vs. investing in the capacity for sustained research and development, and undermining the independence and success of innovative domestic research institutions. In some countries where governments have committed significant investment for health R&D, it’s often not financial, and often not useful. For financial investments, for instance, in 2017, the SciDev.Net reported that Uganda committed 30 billion Uganda Shillings (about USD 9Million) to support innovation and technology, and the first round of grants would be given mostly to individuals who had products in place. But critical voices point out that giving these funds to individuals rather than institutions undermine efforts to develop a sustainable ecosystem for innovation, one that supports individuals and a system that nurtures them.

Some of the sharpest criticism among African scientists, ministers, advocates and other observers say research in Africa too often can be experienced by African scientists as extractive, a ‘slave model’, where foreign funders reap the benefit of African intellectual labour but leave behind few benefits for ordinary Africans. Researchers are sustained by their own governments to continue their work with salaries and operational costs. Those same researchers advance proposals to foreign donors, often in consortia, and may individually benefit with publications, promotion, peer recognition and presentations at international conferences. But the true impact of their labour—the field advances with new tools, products and interventions—is not felt at home. An African scientist quoted in Scidev.net noted “Maybe we should have an incentive system structured differently in research institutions. An innovation is a public good with commercial value and industrial application, but a publication has knowledge value. When we reach an extent where they will use commercial output from innovators other than publication, we shall see more innovations come out.”

The Situation analysis report on the mobilization of resources for health research and development finds that Africa has made progress towards financing for health R&D, especially in the past decade, but many African countries still have significant gaps to address. Of all the sampled countries, the report showed that Malawi had the highest proportion allocated to research in general at 1.06 percent of GDP, while Kenya had 0.79 percent, Rwanda 0.66 percent and Eswatini 0.27 percent. The report has clear recommendations – for policy makers and civil society organizations to address the challenges.

The reports findings and recommendations call for:

a. Increased government funding for health and research, which signals government leadership and commitment, and encourages greater investment from domestic partners

b. Strengthening existing laws, regulations and policies and enacting new ones where needed to guide research

c. Increase the influence of research on government policy by locating research closer to political power and aligning research priorities between researchers and governments

d. Governments must lead and facilitate collaboration between government and the private sector to fund and conduct contextually relevant health research

e. Research in Africa must prioritize benefits to Africans in research and development Incorporate robust accountability structures for efficient use of research resources

f. Advocating collectively for an enabling democratic environment for effective research

g. Strengthen cross-sectoral partnerships among CSOs to advocate for health research and development

h. Strengthen the advocacy capacity of CSOs in health financing and health research

The following are key strategies that advocates should consider:

1. Demonstrate to governments how specific investments are cost-effective, bring health and socioeconomic benefits, and enable broader governmental objectives

2. Explains the consequences of not investing in health R&D, including a slowing economy, reluctance of business and funder entities to invest, a “brain drain” of science and medical professionals, and cascading losses of the R&D benefits to other countries

3. Choose a collaborative approach to ensure that key government officials and policymakers view advocates as assets, partners and problem solvers with whom relationships can be formed towards the realization of health objectives and the mobilization of resources

4. Partner with experts in disciplines such as economics, public finance, business and international development for the strongest possible advocacy for health R&D

5. Strengthen capacity to interrogate and track government funding and actual expenditure on health R&D

The report concludes that governments, among others, in low and middle income countries (LMICs) must prioritize and ensure budgetary allocations to health R&D, beyond the non-financial investments. Budget commitments have the potential to attract additional investments by partners and demonstrate political will. It’s time to champion this work! Join us for the Biomedical HIV Prevention Forum (BHFP) Pre-Conference at ICASA, scheduled for December 6, 2021 at 12:25pm SAST as we dive deep into this conversation and draw collective action points.