In this Mail and Guardian editorial, South African advocates call on the South African government and health department to do its part to expand the provision of PrEP and integrate it into combination treatment and prevention programs before “people are agitated and take to the streets to demand these tools”.

South Africa has rolled out the largest antiretroviral treatment program in the world—about 3.1 million people are now on treatment, according to health department figures.

This is a remarkable, given the earlier years of poor political response. But South Africa still has unacceptably high rates of infections and HIV remains a public health emergency.

Within the general epidemic in South Africa, some specific population groups—such as sex workers, gay men and other men who have sex with men (MSM), discordant couples (where one partner is HIV-positive and one HIV-negative), truckers and people who inject drugs—have higher rates of HIV and require specialised interventions.

The disease takes a particularly devastating toll on the lives of adolescent girls and young women between the ages of 15 and 24, a rate more than four times that of their male counterparts, according to the Human Sciences Research Council’s 2012 National HIV Prevalence, Incidence and Behaviour Survey.

The HSRC survey, also found that more than 400,000 new HIV infections occurred in 2012, bringing the number of people infected in South Africa to 6.8 million in 2014.

A disturbing picture

These statistics present a disturbing picture of the HIV epidemic and our response. In delaying the implementation of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), has South Africa failed to embrace the wisdom of science?

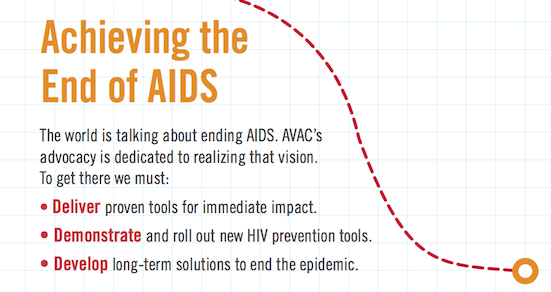

This new option for HIV-negative people at substantial risk of HIV infection is a combination antiretroviral drug, TDF/FTC, taken once a day, which can drastically reduce their chances of becoming infected. Research studies show that, when this two-in-one pill is taken correctly and consistently, it is more than 90 percent effective.

There have been unexplained delays by the Medicine Control Council to approve and license TDF/FTC as pre-exposure prophylaxis and the department of health’s response to South Africans voicing their demand for this action has been silence. The council should approve TDF/FTC before the end of this year.

New guidelines

Advocates welcomed the World Health Organisation’s (WHO) new guidelines for HIV treatment, released in September. These recommend that: “Oral PrEP… should be offered as an additional prevention choice for people at substantial risk of HIV infection as part of combination HIV prevention approaches”.

The new guidelines have broken the silence among policymakers on the future of pre-exposure prophylaxis in South Africa. Following their release, Yogan Pillay, the health department’s deputy director-general for HIV, endorsed the WHO guidelines in an article in the Mail & Guardian. This demonstration of commitment is an important step in realising our dreams about providing pre-exposure prophylaxis.

As HIV prevention advocates, we talk to many people, including potential users of TDF/FTC. We hear from a host of people from all walks of life who are demanding pre-exposure prophylaxis. They want to know when the drug will be available in South Africa and how they can get access to it. These questions have been previously been impossible to answer, but now we hope to work with health department. Will the department follow through on its commitment and the ethical imperative to provide medicine that is a crucial step in confronting the HIV epidemic?

We would like to see such a programme rolled out in the shortest possible time, and through existing structures, where possible.

We know that implementation of this new intervention will not be easy. It requires political will, dedicated advocacy, domestic sources of funding and international donor commitment.

More importantly, investment must be based on decisions that are driven by evidence rather than sentiment. The health department will need support from a variety of stakeholders—much of which can and will come from the huge groundswell of civil society support for the implementation of a pre-exposure prophylaxis programme.

Timeline

As we prepare to support the department in planning and executing such a roll-out, we have questions. What are the department’s plans for this? What are the timelines? Has the department started seriously with advocates in the provinces? What are the advocacy issues that civil society can push?

We need effective models to deliver PrEP. Demonstration or pilot projects in South Africa and around the world will provide us with the knowledge to guide a roll-out in real-world settings. The health department can also take advantage of data on existing public health programmes that can be adapted for providing TDF/FTC.

Some organisations that already provide comprehensive HIV prevention services are suggesting that the department use existing structures and services to start and expand the provision of PrEP and integrate it into combination treatment and prevention programs.

Within these organisations, there are champions who have already established positive working relationships in communities. They can help to identify barriers to implementing and recommend strategies to address the barriers.

Recommendations

Young women tell us, “We recommend that youth-friendly clinics be established and that health staff be sensitised about the unique needs and problems that young people face.” Similarly, sex workers have suggested that TDF/FTC should be provided “within user-sensitised facilities” and, where possible, through mobile clinics. Men who have sex with men are calling for the medicine and some are already getting it from private clinicians through “off label” prescriptions.

As advocates, we will continue our work to educate the public about TDF/FTC, how to get it and how it can further strengthen existing HIV prevention efforts. But we know that there is more to be done through working closely with people and with social marketers.

We will also continue preparing for the results of a vaginal microbicide ring study expected early next year. The vaginal ring, another form of PrEP, slowly releases the antiretroviral drug dapivirine over the course of a month. If proven safe and effective, the vaginal ring could expand options for women-initiated HIV prevention methods.

Civil society is working with the International Partnership for Microbicides, the organisation which developed this technology, and other partners who conducted microbicide research among South Africans to plan for the results and introduce the product if it is proven effective. No microbicide has yet been licensed for use.

We acknowledge South Africa’s remarkable success in fighting HIV. There is now opportunity to build on these successes by taking advantage of new innovations such as TDF/FTC to reduce the chance of infections and save on treatment costs. HIV-negative South Africans have a right to use this life-saving intervention now.

We should not have to wait until people are agitated and take to the streets to demand these tools.

Will South Africa show global leadership and take immediate action to get PrEP into people’s hands? Or will our collective conscience be haunted in years to come, knowing we could have averted new infections and saved on costs of lifetime HIV treatment and sickness? The science is clear that TDF/FTC works when taken correctly and consistently; now we must follow this evidence and act on it.

John Mutsambi is an AVAC Fellow. AVAC is a US based organisation that advocates for HIV prevention to end AIDS. Brian Kanyemba, Yvette Raphael and Ntando Yola are the leaders in PrEP advocacy in South Africa.

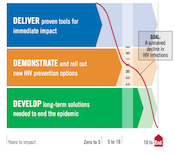

We’ve experienced 20 years of breakthroughs and disappointments in prevention research. A vaccine that many had given up on was the first to provide modest protection. One microbicide everyone hoped for didn’t pan out. Male circumcision and PrEP studies overcame skepticism and, together with antiretroviral therapy, paved the way for a prevention revolution.

We’ve experienced 20 years of breakthroughs and disappointments in prevention research. A vaccine that many had given up on was the first to provide modest protection. One microbicide everyone hoped for didn’t pan out. Male circumcision and PrEP studies overcame skepticism and, together with antiretroviral therapy, paved the way for a prevention revolution.

When AVAC was founded, the only biomedical HIV prevention options for adults were male and female condoms. The pathway for introducing any new strategy was largely unmapped. No one knew where the gaps would be—between trial result and country action, between guidance and financial support. Now we do.

When AVAC was founded, the only biomedical HIV prevention options for adults were male and female condoms. The pathway for introducing any new strategy was largely unmapped. No one knew where the gaps would be—between trial result and country action, between guidance and financial support. Now we do.

Twenty years ago, advocacy for HIV prevention hardly existed. So AVAC helped build a global network of advocates equipped with effective advocacy strategies and the latest evidence.

Twenty years ago, advocacy for HIV prevention hardly existed. So AVAC helped build a global network of advocates equipped with effective advocacy strategies and the latest evidence.

When the world lacked a plan for ending AIDS, we helped create one.

When the world lacked a plan for ending AIDS, we helped create one.

Communities’ support for prevention research can never be taken for granted — it has to be earned. For 20 years, we’ve helped build trust between researchers, funders and communities to speed the ethical development and rollout of new prevention options.

Communities’ support for prevention research can never be taken for granted — it has to be earned. For 20 years, we’ve helped build trust between researchers, funders and communities to speed the ethical development and rollout of new prevention options.