Join AVAC and partners for webinar on May 3 webinar, 10-11:30am EDT where you can engage with researchers who led the studies about this injectable PrEP strategy and advocates who are leading essential advocacy efforts around the introduction of CAB-LA. On the call, lead trial investigators Sinead Delany-Moretlwe from HPTN 084 and Raphy Landovitz from HPTN 083 will provide updates, and we’ll be joined by AVAC’s Emily Bass, Chiluyfa Kasanda from TALC in Zambia, Richard Lusimbo from Pan Africa ILGA, and Sibongile Maseko who is an independent consultant and women’s health advocate based in Eswatini. Register here.

Long-Acting Injectable Cabotegravir for PrEP: Understanding Results of HPTN 083 & 084 and key areas for advocacy

Moving Ahead with Long-Acting PrEP: Webinar and updated resource on CAB-LA research and advocacy

Long-acting injectable cabotegravir (CAB-LA) for PrEP is causing buzz and raising opportunities and questions for prevention advocates. Whether you’ve got questions or want to know what the buzz is about, AVAC has you covered.

We’ve updated our comprehensive primer on CAB-LA: Advocates’ Primer on Long-Acting Injectable Cabotegravir for PrEP: Understanding the Initial Results of HPTN 083 and HPTN 084, and held a May 3 webinar, 10-11:30am EDT where you can listen to the researchers who led the studies about this injectable PrEP strategy and advocates who are leading essential advocacy efforts around the introduction of CAB-LA.

On the call, lead trial investigators Sinead Delany-Moretlwe from HPTN 084 and Raphy Landovitz from HPTN 083 provided updates, and we were joined by AVAC’s Emily Bass, Chiluyfa Kasanda from TALC in Zambia, Richard Lusimbo from Pan Africa ILGA, and Sibongile Maseko who is an independent consultant and women’s health advocate based in Eswatini.

Watch the recording and find the slides here.

As our new primer describes, CAB-LA injections every eight weeks provided high levels of protection against HIV in cisgender women, cisgender men who have sex with men and transgender women who have sex with men. That’s truly exciting. There’s also a lot to learn and understand about next steps. A small number of people who received on-time injections and went on to acquire HIV did not test “HIV-positive” on standard antibody-based HIV tests. An even smaller number acquired resistance to integrase inhibitors—the class that includes cabotegravir and dolutegravir. In addition to these crucial issues, it’s also important to focus on questions of access. For those who want an injectable PrEP strategy, CAB-LA needs to be accessible and affordable.

What do the trial results explain, what still needs to be explored, and what do advocates think needs to happen next? Check out the updated resource and register the webinar to engage with it all!

Make Your Voice Heard: Towards advancing racial equity & diversity in biomedical research

John W. Meade Jr. is AVAC’s Senior Manager for Policy and Kevin Fisher is AVAC’s Director of Policy, Data and Analytics.

In the US, April is National Minority Health Month, and April 11-17th is Black Maternal Health Week. It is well past time to focus on distinct health disparities among Black, Indigenous, and other people of color (BIPOC) and Latinx communities, especially given the CDC’s recent, welcome focus on health disparities and equity. For example, Black people make up 13-15 percent of the United States population but about 27 percent of COVID-19 cases in the US, and the COVID-19 mortality rate for Latinx people is 2.5 times higher than that of white people, just to name a few. These long-standing disparities are rooted in systemic and institutional racism and perpetuated through research, the programs that implement the fruit of research, and the way both are funded. The impact on the HIV field is pernicious. BIPOC and Latinx communities carry an outsized burden and are also excluded from contributing to the solutions. The field is deprived of the insights, knowledge, experiences, expertise, creativity and innovation of BIPOC and Latinx communities—a universe of potential that’s neglected and squandered.

The Biden Administration opened this year with a commitment to address four “converging crises” facing the country: the COVID-19 pandemic, economic recession, climate change, and racial discrimination and inequity. The first two crises are relatively new, but the last is a multi-generational plague crippling this nation. The slow progress toward racial equity and diversity in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) research, and National Institutes of Health (NIH)-funded research has been the subject of many initiatives over the years. Yet a recent NIH-commissioned analysis makes clear that existing policies, procedures and practices continue to perpetuate racial disparities and biases in the grantmaking process. A Black researcher’s chance of winning NIH funding remains 10 percentage points lower than that of applications from white counterparts, and has a lower probability of being awarded the NIH R01 Type 1 funding that is critical to a scientific career, regardless of the investigator’s degree.

On March 1, 2021, as part of the UNITE initiative, the NIH released a Request for Information (RFI) on the approaches NIH can take to advance racial equity, diversity, and inclusion within all facets of the biomedical research workforce, and expand research to eliminate or lessen health disparities and inequities. Responses are due April 23.

A number of HIV organizations have responded to the RFI including AIDS United, the Black Gay Researcher Collective, the National Black Gay Men’s Advocacy Coalition and the Black Women’s HIV/AIDS Network. The Research Working Group (RWG) of the Federal AIDS Policy Partnership, which is a coalition of more than 60 national and local HIV/AIDS research advocates, patients, clinicians and scientists from across the country, including AVAC, has developed a response focused on how racial disparities/biases specifically impact HIV research. The RWG response, signed by over 25 US HIV organizations, can be found here and calls on NIH to:

i. Develop new and nurture existing partnerships or collaborations that NIH could leverage to enhance the NIH-funded biomedical research enterprise within BIPOC and Latinx communities.

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, NIH provided Meharry Medical College, an Historically Black College based in Tennessee, with vital research and technical support to advance development of COVID-19 treatment and vaccines. Investments in research institutions such as Meharry can address barriers to accessing the complex NIH funding mechanism and conduct research that will benefit BIPOC and Latinx communities.

ii. Review and amend existing NIH policies, procedures, or practices that may perpetuate racial disparities/bias in application preparations/submissions, peer review, and funding.

NIH grant applications are notoriously difficult to navigate. BIPOC and Latinx researchers in particular have the “cards stacked” against them, often having limited support and ability to navigate a deeply entrenched, institutionalized and competitive system. More BIPOC and Latinx researchers can be recruited by offering application assistance, this can include streamlined guidance and mentorship from institutions with a track record of successful applications.

iii. Increase support for researchers and research institutions based in Africa.

Given the scale of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Africa, it is critical to develop regional capacity to conduct research on strategies that will improve HIV prevention and care in countries in Africa most impacted by HIV/AIDS.

iv. Diversify HIV clinical trial participant populations.

The NIH is mandated to ensure the inclusion of significant numbers of women and minority populations in all NIH-funded clinical research to the extent that it is appropriate to the scientific study. The HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN) 083 study has been a notable success in reaching very ambitious recruitment and retention targets for highly marginalized communities of color. Building partnerships with community and collaborative engagement to identify problems and develop solutions made this success possible.

v. Incentivize BIPOC and Latinx individuals to become STEM scientists and infectious disease physicians and researchers.

The US government, including agencies such as the Department of Education, must invest in STEM and diversity programs to engage BIPOC and Latinx students from an early age, and address financial and structural barriers that may deter BIPOC and Latinx students from entering the fields of medicine and science.

The NIH must hear responses to their RFI from not only BIPOC and Latinx researchers, but from anyone committed to improving the ways in which HIV research is funded through the NIH. Responses are due April 23 and can be submitted here.

Join us and share your thoughts and feedback with the NIH on how to advance racial equity in biomedical research.

Protecting Global Gains: Abiyamo Alayo: Happy Mother radio show takes community outreach further

The latest edition of Protecting Global Gains, Abiyamo Alayo: Happy Mother Radio Show Takes Community Outreach Further, describes how “mentor mothers” in Nigeria adapted to keep medicines and supplies flowing despite COVID-19 disruptions. Prior to COVID-19, over 100 mentor mothers, trained and supported by PLAN Foundation, were helping build healthy communities in Nigeria. Through direct community outreach, these mentors helped educate people about vital health issues and connected them to HIV testing, family planning, antenatal care, and more. When COVID-19 struck and lockdowns were enforced, this in-person outreach was halted and fears of unwanted pregnancies and disruptions to HIV/AIDS programming began to mount.

To respond to immediate needs, some mentor mothers quickly mobilized to become community-based distributors, delivering HIV medications and other essential supplies, including contraceptives, directly to their clients’ doorsteps. Then came Happy Mother / Abiyamo Alayo, a weekly hour-long bilingual (Yoruba and English) radio show offering a platform for mentor mothers and community health workers to promote understanding of women’s health and to directly address any listener questions. The work did not stop there: listeners to the radio show who expressed concerns about their health were connected to their closest mentor mother for personalized assistance.

Happy Mother / Abiyamo Alayo has been a hit, reaching communities far beyond the area where mentor mothers operated prior to COVID. The program’s success highlights the importance of client-centered services that connect community health and clinical care for maximum impact.

Follow Protecting Global Gains on social media at @hivpxresearch, @theglobalfight, @Amref_Worldwide, and #ProtectingGlobalGains, and consider amplifying these stories on your own social media. Advocates can also explore recommendations from the Frontline Community Health Workers Coalition and do their part to support the vital work of community health workers. Visit www.protectingglobalgains.org to learn more about how to take action.

Can Unprecedented Success in COVID Vaccine Development Boost Prospects for an HIV Vaccine?

Mitchell Warren is AVAC’s Executive Director. This piece first appeared on Science Speaks.

In February 2020, just as the COVID pandemic began its rapid global spread, a major HIV vaccine trial called HVTN 702, or Uhambo, was halted for lack of efficacy. Researchers and advocates had high hopes for Uhambo, building as it did on the RV144 trial, which provided the first evidence that an HIV vaccine could create a partially protective immune response. But Uhambo, like several studies before it, ended in disappointment.

On the same day that Uhambo ended, efforts to develop a vaccine against COVID-19, a disease that much of the world had yet to even hear about, were rapidly taking shape. In less than a year, the unprecedented global response to COVID produced multiple, highly effective vaccines. Yet the Uhambo researchers, in publishing their results last week in the New England Journal of Medicine, were obliged to remind the world that, nearly 40 years after the identification of HIV, there is still no AIDS vaccine:

“The high HIV-1 incidence that we observed in our trial illustrates the unrelenting aspect of the epidemic, especially among young women,” they wrote. “More than ever, an effective vaccine to prevent HIV-1 acquisition in diverse populations is needed.”

The Uhambo researchers are right: the need for an HIV vaccine could not be clearer. And the COVID-19 experience provides an important new roadmap for how to get one.

First, it’s critical to acknowledge that COVID vaccines exist because of decades of investments and advances in HIV vaccine research. HIV vaccine researchers and research networks led the scientific effort; HIV funding networks, scientific collaborations and clinical trial infrastructure sped COVID vaccine development; years of effort by HIV researchers to understand human immune responses guided the effort; vaccine platforms such as mRNA and Adeno26, developed and advanced through HIV vaccine studies, were repurposed for COVID prevention; and community advocates provided the expertise that helped enroll massive clinical trials and guide COVID vaccines through global regulatory processes.

So why do we have several effective COVID vaccines today, and none for HIV?

The clearest, most direct answer is that the scientific challenge of developing an HIV vaccine is much greater than it was for COVID. SARS CoV-2 is a relatively simple virus. HIV’s rapid mutations and capacity to evade natural immunity make it the most complex viral target ever encountered.

While the scientific challenges of HIV vaccine research are clear, however, so too is ample evidence from the COVID experience of what is possible. Simply put, the world is better positioned today than ever before to develop an HIV vaccine — if the HIV research effort can build on the COVID experience the way that COVID built on HIV.

Step one: we need a global effort to replicate the unprecedented level of funding, coordination, scientific collaboration and global political will that guided the fast-track development of COVID vaccines. With COVID, billions of dollars in research funding materialized overnight. Academic researchers, pharmaceutical executives and political leaders made the vaccine a priority, identifying and addressing obstacles to success in real-time. The result: there have been more large-scale COVID efficacy trials in one year than in more than 30 years of HIV vaccine research.

Next, financial investments were committed in advance of scientific answers, accelerating every stage of the COVID vaccine research process and condensing the gaps between each critical step from years to days. By contrast, it took seven years from getting the results of the RV144 trial before HVTN 702 even began.

Then, HIV vaccine research must move more rapidly to incorporate the latest scientific discoveries — from the COVID vaccine effort, and from other fields of study.

The cutting-edge mRNA technology used in several successful COVID vaccines, for example, holds great promise for HIV vaccine research. At the recent Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, the US National Institutes of Health and Moderna scientists presented initial data that an mRNA vaccine protected monkeys against HIV-like virus.

Two large studies of the Janssen Adeno26 HIV vaccine candidate, using another platform that was successfully employed against COVID, are also underway. When they report results, the field must be prepared to act on those findings with the same urgency, as well as the political and financial will that defined the COVID vaccine effort.

Studies that do not produce new prevention products, such as HVTN 702 and the recent Antibody Mediated Prevention (AMP) trial, can also offer critical insights into the type of immune responses that can provide durable protection against HIV, and can feed critically important data into a faster, more dynamic HIV vaccine effort.

Finally, planning for success must be the new normal. In this respect, the HIV vaccine effort can learn from COVID’s failures as well as its successes. Products don’t end epidemics; programs that deliver equitably and at scale do.

The infrastructure and urgency to manufacture and distribute COVID vaccines to translate great science into actual public health impact for all continues to lag tragically far behind research efforts, creating a bumpy rollout, vaccine shortages and significant equity issues. Avoiding the same mistakes for HIV will require expanding and sustaining current investments in vaccine manufacturing and distribution, and strengthening efforts to ensure that community leaders are integrally involved in efforts to introduce and ensure access to successful HIV vaccines.

The persistently high rates of new HIV infections among participants in the Uhambo and AMP studies are stark reminders that developing an HIV vaccine is critical. The COVID vaccine experience provides critical, real-world examples of how to get it done.

New Resources on AVAC.org

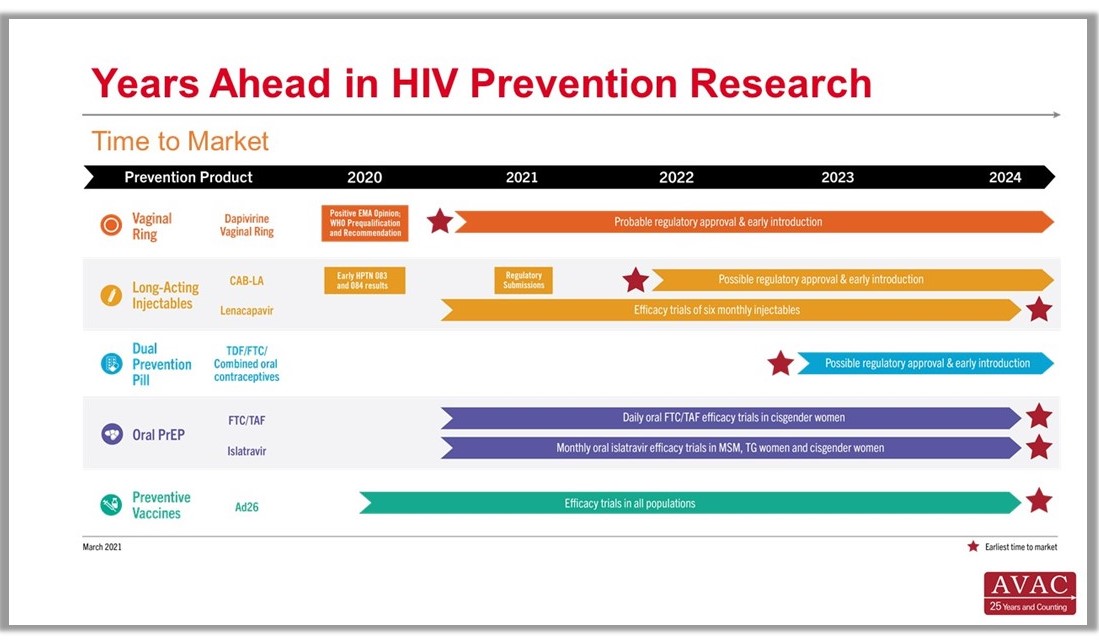

AVAC has several new resources covering a gamut of cutting-edge issues for the field. An up-close look at the science covered at CROI; a handy snapshot of multipurpose technology (MPTs) moving through the research pipeline; a new infographic on “time to market” for HIV prevention products furthest along in development; and a special publication of Good Participatory Practice fitted to address COVID-19 trials. Read on for details and links for these timely resources.

Time to Market Infographic

Years Ahead in HIV Prevention Research: Time to Market – The latest addition to our extensive infographic library is this new timeline showing the potential time points when the next-generation of HIV prevention options might find their way into new programs. This new graphic complements the HIV Px Research, Development and Implementation pipeline snapshot and The Years Ahead in Biomedical HIV Px Research trials timeline.

MPTs Making Headway

Advocates’ Guide to Multipurpose Prevention Technologies – Check out this guide to learn about four areas ripe for advocate involvement and get a snapshot on the status of MPT research and development, and data on investments.

Good Participatory Practice in the Age of COVID-19

Essential Principles & Practices for GPP Compliance: Engaging stakeholders in biomedical research during the era of COVID-19 – This guide to support stakeholder engagement in COVID-19 research is built from the Good Participatory Practice Guidelines for Biomedical HIV Prevention Trials (GPP). This new document responds to needs expressed by both researchers and advocates as COVID-19 research progresses with unprecedented speed and urgency. To mark the launch of this new document, AVAC hosted a webinar earlier today, which included diverse perspectives on the importance of GPP within COVID-research and beyond. Watch the recording here.

CROI in Focus

The Personal is Planetary: CROI and COVID one year on – This blog by AVAC’s Emily Bass gives context and perspective on the science and advocacy that defined the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections in 2021. From a call for vaccine equity to a deep dive into the findings on cabotegravir as long-acting injectable PrEP, read Bass’s blog for a picture on where the science and advocacy is moving.

We are also happy to report that, in response to community requests, CROI organizers have agreed to make all recorded content from the meeting available on April 15—five months earlier than initially planned. And, if you missed it, check out the recordings from the Daily Research Updates for advocates on AVAC’s special CROI page.