Anna Miti is a journalist, media trainer and advocate. She is the current chairperson of the Health Communicators Forum of Zimbabwe. She works with the Humanitarian Information Facilitation Centre to convene media science cafes in Zimbabwe.

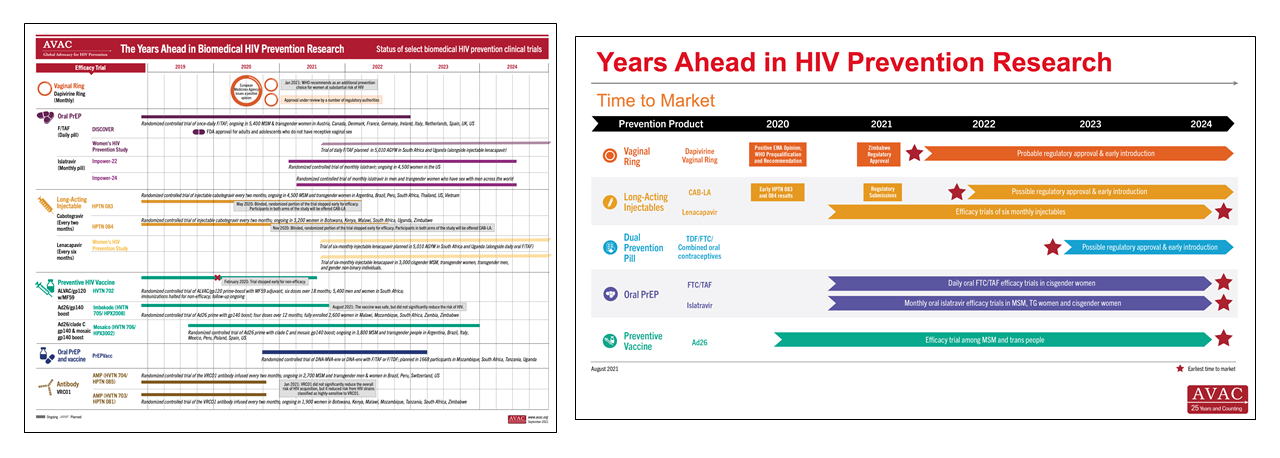

In July 2021, The Health Times of Zimbabwe reported that the Medicines Control Authority of Zimbabwe approved the monthly Dapivirine Vaginal Ring for use as an HIV prevention tool, making Zimbabwe the first country to do so. This news is a milestone in a longer process of approvals and recommendations that was triggered when the ring received a positive scientific opinion from the European Medicines Agency in July 2020 for its use among women ages 18 and older in non-EU countries with a high disease burden. Next came WHO prequalification in November of 2020. Then, in January of 2021, WHO issued a recommendation for the ring as an additional prevention choice for women at substantial risk of HIV infection. Following these actions from the WHO, news of the approval of the ring in Zimbabwe generated a lot of excitement, locally and elsewhere, as this tool is one of the few HIV prevention methods that are solely within the control of women. The ring can be used covertly or overtly to reduce their chances of getting HIV.

I am excited too, but I’m not sitting down to rest with congratulations on my lips.

There is a popular song in Zimbabwe called Kure whose lyrics go “kwatinobva kure, kwatinoenda kure”—loosely translated to mean, “We have come a long way, but we still have a long way to go”. I’m singing that song as I consider the news of the approval of the Dapivirine Vaginal Ring in Zimbabwe. This journey has been really long. People have been struggling to push forward an option women control and can use discreetly for decades.

Over the years, some microbicide and PrEP studies showed promise, others ended with disappointing results (see box). But advocates, researchers, champions of women’s health, of women’s rights, of HIV prevention, we all pushed on. Researchers were exploring drugs such as tenofovir, using different delivery methods such as gels and films. It was not until 2016, when the results of two large-scale studies of the Dapivirine Vaginal Ring, ASPIRE and RING, that a woman-controlled option showed significant efficacy in HIV prevention. Five years later, the world has its first approval. Now, in the days, weeks and months to come, so much needs to be done. Women who need the ring must be able to find it when and where they look for HIV prevention, and they need to know about it, with every question answered, to feel empowered to choose it.

What is the Dapivirine Vaginal Ring?

The ring is made of a flexible silicone matrix polymer and contains the antiretroviral (ARV) dapivirine, which is slowly released over the course of a month. The ring delivers dapivirine directly at the site of potential infection, with a very low amount of drug ever absorbed into the body (known as systemic absorption). Women insert the flexible, long-acting ring themselves into the vagina and replace it every month. Two Phase III studies found that the ring reduced the risk of HIV and was well-tolerated with long-term use. The Ring Study, led by IPM, found that the ring reduced overall risk by 35 percent, and ASPIRE, conducted by the US National Institutes of Health-funded Microbicides Trials Network (MTN), found that the ring reduced overall risk by 27 percent. Open-label studies showed that, with higher adherence, the efficacy rates can be higher: the DREAM and HOPE open-label extension trials (OLEs), which enrolled former participants of The Ring Study and ASPIRE, showed increases in ring use compared to the earlier studies. Modelling of this data showed increased efficacy—by over 50 percent across both studies—compared to the earlier studies.

Furthermore, interim results from REACH show encouraging levels of adherence to both the Dapivirine Vaginal Ring and oral PrEP. (About 50 percent used the ring for the full month, another 45 percent used it at least some of the time. About 58 percent of oral PrEP takers took the pills four days or more per week, another 40 percent took the pills 1-3 days per week). The study assessed safety, adherence and acceptability of both products among adolescent girls and young women in Africa. Other studies include the DELIVER and B PROTECTED studies to assess the ring’s safety among pregnant and breastfeeding women. The ring has potential for further development into longer-acting rings and into a multi-purpose prevention option which can potentially prevent both HIV and pregnancy.