“Science has delivered solutions. The question is: When will we put it into practice?”

So says the last line of the Vancouver Consensus Statement, a stirring call for expanding access to antiretrovirals for treatment and prevention as part of a comprehensive response to AIDS. AVAC signed the statement, released at the start of this year’s conference of the International AIDS Society. So did virtually every notable scientist and physician in the field. And we firmly believe in the contents of the statement.

Over Sunday and Monday pre-conference satellite sessions and in the official program, we heard a lot of science. On Monday, there were presentations of data from HPTN 052 and START—two complementary trials of ART in people living with HIV. There were also data from the ADAPT and IPERGAY PrEP trials and a press conference looking ahead to news from later this week.

For all of this, the Vancouver Consensus Statement is the backdrop—as is the news, released by UNAIDS just prior to the launch of the conference, that the global total of people initiated on ART has exceeded 15 million, and that incidence has begun to drop in some places.

Overall, it is a very good time to be on the side of scientific solutions to the HIV pandemic. And that’s where AVAC stands. But listening closely at the conference and in recent months, we’d offer this additional formulation of the consensus statement’s closing line: “Science has delivered the questions. The solution is: Not shying away from the answers.”

One of the primary solutions that science has delivered is the use of antiretroviral therapy for people living with HIV, both for their own health and to reduce the risk of onward transmission. In a special presentation on Monday (The Strategic Timing of Anti-Retroviral Treatment (START) Study: Results and Their Implications (Monday 20 July, 11:00-12:30), Jens Lundgren (University of Copenhagen) presented data from the START trial, which showed significant benefits for people living with HIV who started ART regardless of CD4 cell count, versus those who started treatment as indicated by the guidelines where they lived. As described in May, when data from the study were first reported, immediate initiation more than halved the risk of serious adverse events, serious non-AIDS events, or deaths.

This is the first major meeting since the START data started making waves (between START and PrEP, this may be the most pun-able conference to date), reaffirming global campaigns to expand ART coverage and to make ART the cornerstone of efforts to end AIDS.

If START has a twin, it is HPTN 052, which also saw data presented on Monday. Mike Cohen (UNC and HIV Prevention Trials Network) delivered the complete findings from HPTN 052, which first reported interim results in 2011 (View slides and abstract via the Conference Programme, session MOAC01: TasP: Just Do It. Monday 20 July, 11:00–12:30)

In that preliminary report, immediate initiation of ART (in this trial, at CD4 cell counts above 350) dramatically reduced the chances that an individual would pass HIV to his or her primary partner.

In the data Cohen presented here, the initial finding holds true. Over the course of the trial, there were eight “linked” transmission events (where the virus acquired matched that of the partner enrolled in the study) in couples where the HIV-positive partner had initiatied ART. Where transmission did occur, it usually happened in the context of incomplete virologic suppression—either a person had started ART too recently to be completely suppressed or because of adherence challenges.

The bottom line: virologic suppression makes HIV transmission between individuals where one person is living with HIV and the other is not highly unlikely. The treatment that has a prevention benefit is also good for the individual—so on every count, the science appears to have provided the solution.

And yet. The real world is a decidedly unscientific place.

In HPTN 052, there were 26 unlinked transmission events, where a person with a known HIV-positive partner acquired HIV from outside the primary partnership followed in the study. So having one partner who is virologically suppressed isn’t protective for an HIV-negative person who, for a variety of reasons, may have other partners and/or other sources of risk, such as injection drug use.

This reality is one of the many places where science and social, cultural and personal realities demand multiple solutions. The number of unlinked cases of HIV is a reminder that people exist in complex realities, with multiple partners and various behaviors.

Another powerful reminder of this context came at a pre-conference satellite on the global status of women’s access to ART. That session presented preliminary findings from an ongoing investigation commissioned by UN Women and carried out in collaboration with the ATHENA Network, Salamander Trust and AVAC. Combining a participatory methodology in which women living with HIV defined, delivered and assessed questions about health care experiences and an in-depth literature review, the work to date shows that women are being reached by ART but that the rights-based framework that allows them to remain on ART after initiation is, in many instances, lacking.

What to do with these data?

One answer does lies in science. Earlier this year, at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, the investigators of the Partners Demonstration Project presented the results of their combination PrEP and treatment study in which the HIV-negative member of a serodiscordant couples was offered PrEP as a “bridge to ART” for the person living with HIV. Right now, the data say that PrEP reduces risk of HIV acquisition regardless of who your partner is or how many partners you have (for more on PrEP, see below). And it turned out that, over the course of the study, very few new cases of HIV occurred. For 48 percent of the time, couples were using PrEP alone. PrEP and ART overlapped during 27% of the time, ART was used alone 16% of the time, and neither was used 9% of the time.

WHO did not formally publish their new ARV guidelines at this meeting. However, Gottfried Hirnschall, who directs WHO’s HIV department, did say that additional formal guidance on both PrEP and ART would be released by the end of the year. It is even possible that “rapid advice” could be available sooner—perhaps even in a matter of weeks. Hirnschall anticipated that these new ARV guidelines would recommend the offer of treatment for all adults and adolescents regardless of CD4 count as well as PrEP being offered as an additional prevention choice for people at substantial risk of HIV infection.

As Ambassador Debbi Birx, head of the US PEPFAR program stated in her Monday morning plenary, “Don’t wait for the paper” from WHO or other agencies. “Act on the science and evidence now.”

Acting on science is, as Ambassador Birx and other speakers have noted, just part of the solution. Success depends on non-scientific solutions that are, in some cases, getting lip-service but struggling for real traction today. Women in the global survey described above consistently reported the benefit of peer-delivered treatment literacy, non-stigmatizing sexual and reproductive health care, and rights-based care for all women, including those who aren’t pregnant when they enter the health system.

The science, if we really listen, says something slightly different. It says that ART for people living with HIV and PrEP for people who are at risk, and peer-delivered treatment literacy, and rights-based health care environments for women, men, young people and all key populations can begin to end the epidemic—if and only if other strategies are scaled up at the same time.

PrEP Talk: Promising, Perplexing

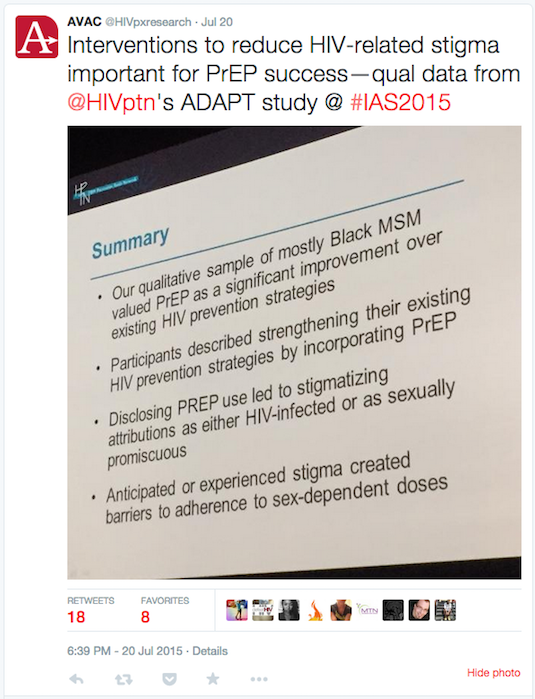

Monday was also a big day for PrEP data (slides can be downloaded from the session MOAC03 from the online conference programme), with data from the ADAPT trial that evaluated various dosing strategies, including once-daily, fixed intermittent dosing and event-driven dosing. The study enrolled South African women and gay men and transwomen in Thailand and the US. Overall, people were able to take PrEP, reported principal investigator Bob Grant. Individuals who were counseled to take the drug on a daily basis had a higher coverage of sex acts than those who were advised to use a non-daily strategy. For this group, the missed dose was usually post-sex—a finding that echoes reports from women who participated in the FACTS 001 trial of 1% tenofovir gel, which also tested a coitally-related dosing schedule. In both ADAPT and FACTS 001 cases, the dose after sex proved difficult—participants weren’t at home and/or weren’t in the emotional or physical space where they felt they could swallow a pill or insert a gel.

The good news from ADAPT is that PrEP continues to be feasible and acceptable in a variety of settings and demographics—bolstering the call for this strategy to be rolled out as an additional prevention option for all individuals at high risk.

Of concern and for careful tracking by advocates, is messages coming from the podium that PrEP may not work as well for women as it does for men whose primary risk is via anal sex. It is clear that women need to take daily oral PrEP for longer periods of time before they have protective levels in their vaginal tissue. It is also clear that adhering to a daily oral regimen may be difficult for some women, just as it is for some men. But what’s happened over the past few days with casual references from NIAID Director Tony Fauci and other leading scientists is a sowing of confusion that appears to contradict the US FDA recommendation and data from the Partners PrEP and TDF2 trials that found comparable protection for men and women.

Sometimes science raises questions, and we’re all for these questions coming to light. But it’s essential that the language be clear and that the way to certainty be mapped out. Right now, the discussion feels more risky than scientific—at a time when science is supposed to reign.