In this Advocates Network, a blog by AVAC’s Kevin Fisher offers a deep dive into an innovative model, SPARC, to show the impact of advocacy.

In September, the publication New Directions for Evaluation featured an article on Pushing boundaries: Advocacy evaluation and real-time learning in an HIV prevention research advocacy coalition in sub-Saharan Africa. Written by former AVACer Jules Dasmarinas and consultant Rhonda Schlangen, the article discusses Simple, Participatory Assessment of Real Change or SPARC, a new model for evaluating the impact of advocacy.

Launched in 2017 as part of our Coalition to Accelerate and Support Prevention Research (CASPR), SPARC offers participants an inclusive process to gain insights, mark progress, and identify successes in advocacy work that can be difficult to assess. Advocacy wins are not always found in the number of new laws passed or dollars distributed. The most important steps sometimes cannot be counted, but they can be understood. Read Kevin’s blog to learn more…

Putting the “L” in Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning (MEL) — a journal review of AVAC’s SPARC program

By Kevin Fisher

Measuring the impact and meaning of advocacy can be difficult. Often goals are achieved or real progress is made, but documenting the role of advocates in those successes can be a challenge. At the same time, campaigns may not achieve every goal to change policies, fund programs or pass legislation, but still have advanced an issue, broken new ground or taken important steps. Those evaluating campaigns may struggle to see and show the impact of advocacy or the signals of progress. Yet it’s critical to assess strategies in real time. At AVAC, we maintain a close eye on our work, gauging both success and areas where more attention or different thinking is needed.

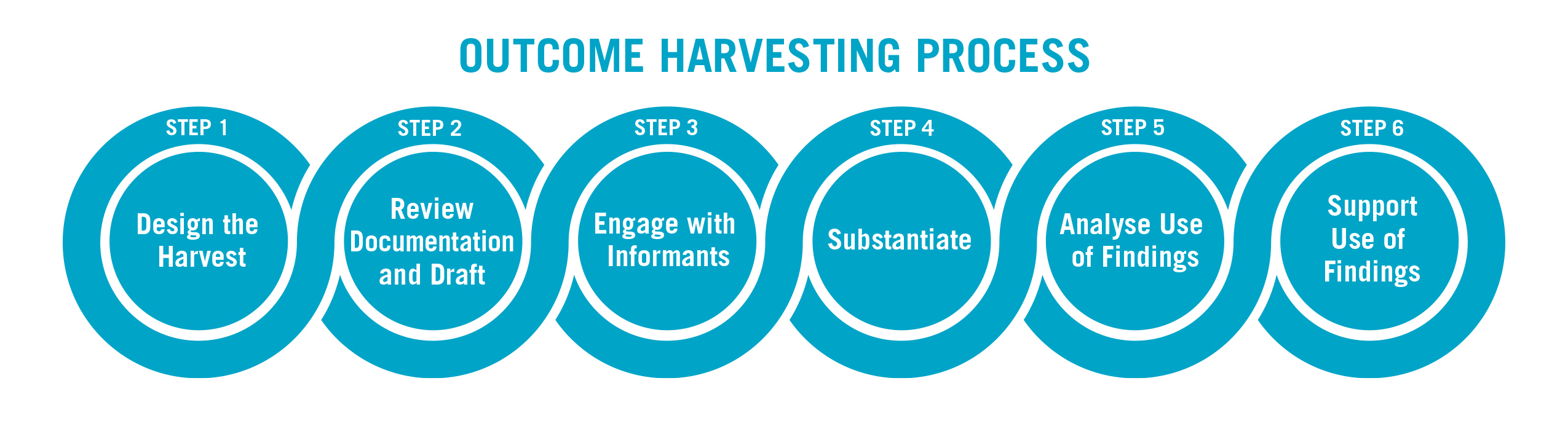

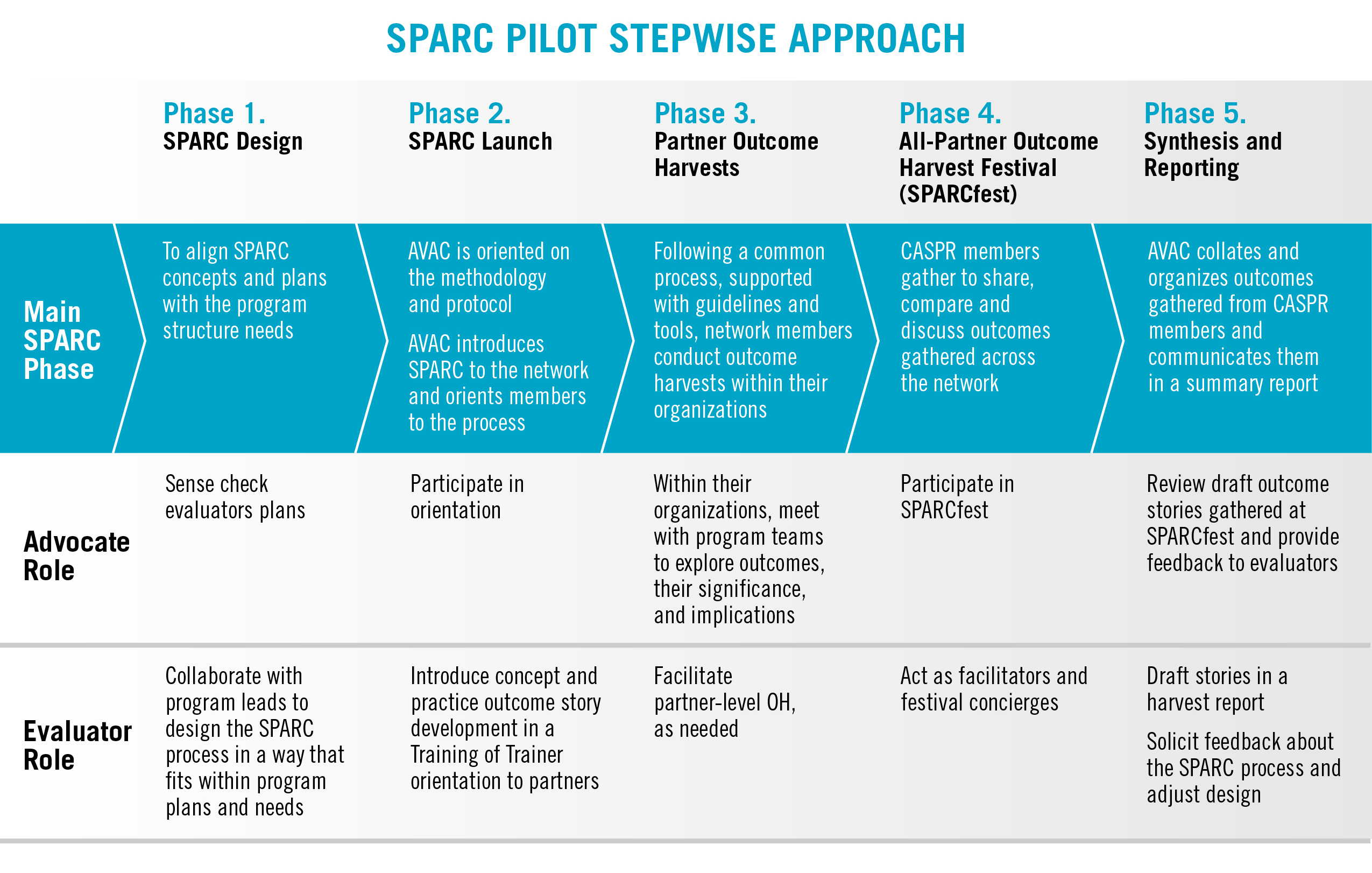

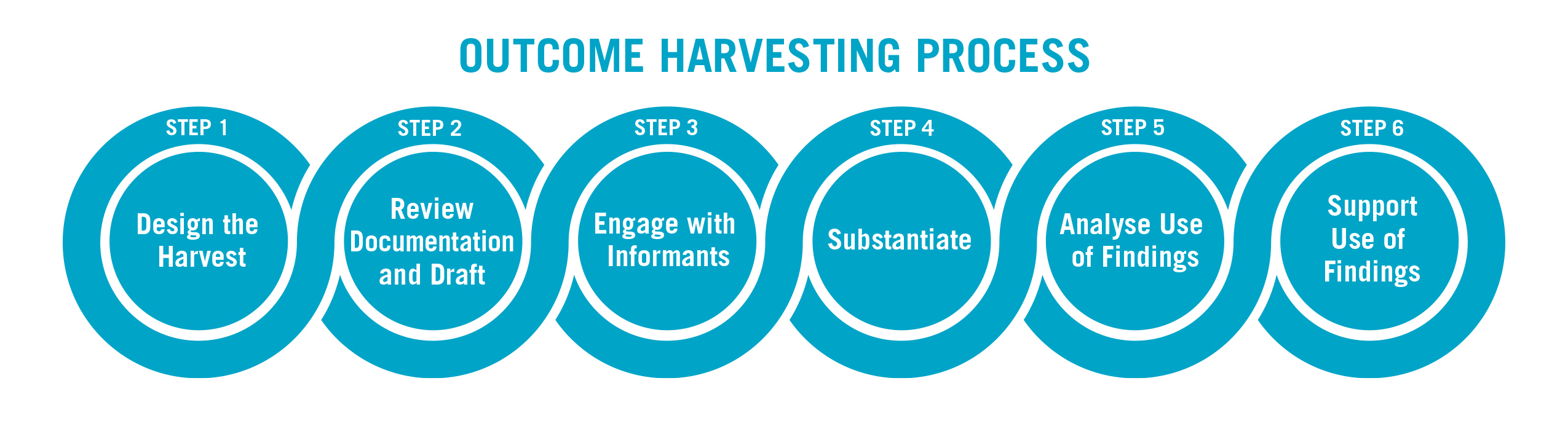

Through the Coalition to Accelerate & Support Prevention Research (CASPR), designed by AVAC in collaboration with key partners and supported by USAID, we created an evaluation tool entitled Simple, Participatory Assessment of Real Change, or SPARC. It’s a participatory system designed to identify outcomes and place advocates at the heart of the evaluation process. As used in CASPR, SPARC harvests “outcome stories” from partners, reviewing these stories across the CASPR network in sessions dubbed a SPARC-fest. Fellow advocates hear the stories, provide feedback, ask questions and test ideas. It is, in a way, a system of peer review for advocates.

Former AVAC staffer Jules Dasmarinas and consultant Rhonda Schlangen discuss AVAC’s SPARC program in a special issue of <New Directions for Evaluation. Pushing boundaries: Advocacy evaluation and real-time learning in an HIV prevention research advocacy coalition in sub-Saharan Africa and it’s an important read for advocates.

Why SPARC?

In 2016, AVAC received funding from the US Agency for International Development (USAID) to develop and implement the CASPR program. CASPR began with its own monitoring evaluation and learning (MEL) system to document outcomes and track indicators of progress. But given the breadth of CASPR partners, AVAC sought a more participatory and inclusive approach that would capture nuances and share lessons for success. SPARC grew from this impulse. SPARC provides a platform for all CASPR members to identify signs of progress and frame outcomes across the Coalition’s priorities. SPARC enables CASPR members and AVAC project staff to see themselves as active contributors in the evaluation process. SPARC demystifies evaluation, expands the discourse, cultivates innovation and informs the advocacy.

As Jules and Rhonda found, SPARC highlighted the following:

- Participants are connected through shared goals and are incentivized to invest in developing relationships and trust. This enables SPARC participants to build off a common foundation and use the process to develop a more nuanced and useful analysis of their collective progress.

- SPARC is integrated into forums that CASPR members use to collaborate and plan their work. This enables SPARC to seamlessly support planning. SPARC is learning that leads to action. By demonstrating immediate application and benefits, SPARC is less likely to be stigmatized as an evaluation process.

- Program managers intentionally calibrate SPARC to integrate and balance with other demands on members’ time.

- Evaluators take a “work ourselves out of a job” approach to ensure focus is on support, keeping an eye on expanding member ownership of the SPARC process.

Where to, SPARC?

At AVAC partner our commitment to SPARC is ongoing. PZAT, has an initiative that is adapting SPARC to its work with the COMPASS Africa project. PZAT, AVAC and others are continually updating our overarching agenda for monitoring, evaluation and learning across all that we do. It’s essential work. Advocacy programs often face erratic funding and questions about their value. Rigorous and multiple strategies for evaluating advocacy are important both to prioritize effective work and to make the case for supporting advocacy. By design, SPARC is a dynamic approach and can be adapted to other coalitions or movements that aspire to learn from all voices in the evaluation process, a model with much to offer the field. New tools for evaluating advocacy, like SPARC, help advocates show the pace of progress and demonstrate real impact on their way to achieving major goals.