This post first appeared on The Huffington Post.

World AIDS Day 2015 comes at a watershed moment in the fight for the health of people living with HIV and for the health of all the citizens of this planet. The two are intimately related: HIV has, for the last three decades, defined the landscape of ambitious, collaborative and innovative responses that marry science, rights, community-based responses and structural change. Ultimately, these responses can be leveraged to improve health everywhere, but only if we continue to make real progress in battling HIV.

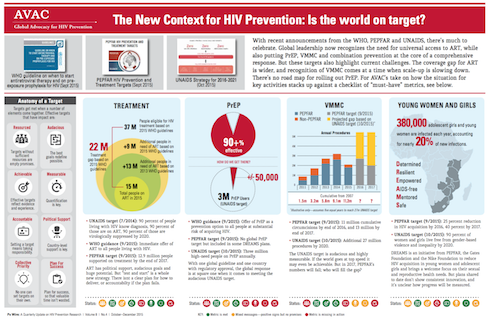

In recent years, collaborations between research teams and thousands of volunteers in clinical trials have yielded insights into how to use HIV prevention and treatment options to end the epidemic. These insights have led to the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) “Fast-Track” approach to ending the epidemic, which sets ambitious targets for a range of interventions, including 27 million voluntary medical male circumcisions by year 2020, three million people on daily oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) annually, major reductions in violence against women, improvements of human rights and, of course, the 90-90-90 targets for 2020: 90 percent of all people living with HIV will know their HIV status, 90 percent of all people with diagnosed HIV infection will receive sustained antiretroviral therapy (ART) and 90 percent of all people receiving ART will have viral suppression.

The world has gotten this far because of massive investments in the HIV response. To actually end the epidemic, though, it is imperative that we resist complacency, cutbacks in funding and a sense that, on any level, our work is done.

Over the last 15 years, the Millennium Development Goals guided the global response to development. Health, including controlling HIV, figured prominently in these goals. In September, the members of the United Nations adopted the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which will guide policy and funding for ending poverty everywhere over the next 15 years. Health is one of 17 goals. To meet it, funders, implementers and country governments will need to be smarter with investments in HIV/AIDS. This means working side by side with people living with and most affected by HIV to develop rights-based approaches and efficient and community-supported service delivery models. And, it means thinking beyond any single health issue and toward integrated approaches that both fight HIV and contribute to ending poverty, hunger and inequality.

This integrated, rights-based approach is needed for all the SDGs. But just as HIV has transformed the way that the world thinks and acts on a single issue, it must also be the leading edge of the pursuit of even more ambitious targets: end epidemic rates of new HIV cases, but also begin to change the quality of life for people everywhere.

Is this a lot to ask of the response to a single virus? Perhaps. But HIV is a virus that reveals the fault lines of societies. HIV follows poverty, stigma, discrimination, criminalization and inequity. Treating HIV effectively means addressing these issues. In many parts of the world, girls and young women are at particular risk, as are men who have sex with men, transgender individuals, sex workers and people who inject drugs. A human-rights-based approach that engages these key affected populations is the basis for a sound, effective response.

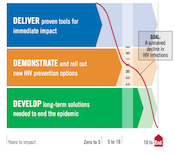

Successful achievement of both the SDG health goal and the UNAIDS Fast-Track targets hinges on innovation. Here, too, the HIV response lays tracks for the path to true global change. Over the last few years, the HIV prevention, care and treatment cascade has emerged as an effective tool for describing the status of the response, influencing policymakers and guiding investments in treatment and prevention. Consistent use of effective ART both improves the lives of those living with HIV and dramatically reduces the chance of transmitting the virus to others. New World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines recommend that people with HIV start ART regardless of their stage of infection. WHO also provided a huge step forward for daily oral PrEP by recommending this proven intervention for all people at substantial risk of HIV infection. More recently, UNAIDS included PrEP in its prevention targets, while the US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) Scientific Advisory Board just released a strong recommendation for PrEP.

Delivering daily medications to both HIV-positive and HIV-negative people in programs that are supportive, accessible and sustainable is a major challenge. But, it can be done. And if it can be done for HIV, it can be done for many other strategies, too. Today’s HIV investments are increasingly focused on creating platforms for health delivery as part of a comprehensive approach to women’s sexual and reproductive health.

Happily, these investments will not only increase the impact that existing interventions can have today, but will also lay the groundwork for eagerly anticipated ARV-based microbicides, especially the vaginal ring with dapivirine, if and when it is demonstrated to be efficacious in clinical trials that will report out early next year.

While the range of options for impacting HIV has grown tremendously, additional research is needed to make things simpler to use, to expand choices and to make health a reality for all. Here, too, HIV is aligned with the broader health response, which seeks to expand access to effective vaccines and durable cures to a range of other diseases. We believe the same tools—a vaccine and a cure—can and must be pursued for HIV.

The broader goals of the SDG era will likely see increased attention on integrated programs that combine multiple health programs, rather than disease-specific programs, with links to education and social and economic development efforts. Smart investments to sustain the momentum for HIV/AIDS control will strengthen health systems and contribute greatly to ending poverty, hunger and inequality, moving the world closer to ending HIV/AIDS once and for all.