This infographic shows that PEPFAR’s increased investment and creation of a budget code resulted in improved scale-up of VMMC (VMMC). A budget code could have the same impact if applied to PrEP initiations.

PEPFAR-Funded PrEP and VMMC Services in 14 Priority Countries

New Resources on AVAC.org

Here’s a roundup of new resources on AVAC.org and PrEPwatch.org!

Vaccine Equity: More must be done now!

- More than 175 leading scientists, civil society leaders and organizations, including AVAC, issued a letter to the White House on August 10th demanding bold and immediate new steps to scale up mRNA vaccine manufacturing around the world.

- The Washington Post also reported on this effort to push the Biden Administration to meet key demands, including a commitment to establish the capacity to manufacture 8 billion doses a year of mRNA vaccines before 2022.

CAB-LA and Implementation Science: New options must be paired with smart rollout

- The published results of HPTN’s 083 study of injectable cabotegravir among cisgender men and transgender women was published on August 12th in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM).

- The results were accompanied by an editorial from CAPRISA’s Quarraisha Abdool Karim, stressing the need for implementation science to make sure new PrEP options reach those who need them.

- Find background and context on CAB-LA in AVAC’s Advocates’ Primer on Long-Acting Injectable Cabotegravir for PrEP. And check out a suite of new resources on PrEPWatch.org from our Prevention Market Manager project that draw insights from a decade of experience with oral PrEP programs, with implications for CAB-LA and other next-generation prevention options.

Protecting Global Gains: Resilient health systems look at the whole picture

The latest installment of stories of adaptation among health systems during COVID is up, Flexible programming gives young women in Rwanda the tools they need to get through COVID-19. The story showcases one Rwanda program under PEPFAR’s DREAMS program where the vocational training in tailoring, offered alongside traditional healthcare, gave young women both skills that were needed during the pandemic and critical social support in the midst of lockdown.

The Ethics of Trial Design: Where PrEP fits in for next-generation prevention trials and more

AVAC is taking a long look at two new guidance documents and their implications for HIV prevention trials: The HPTN’s Ethics Guidance for Research and from UNAIDS/WHO Ethical Considerations in HIV prevention trials.

- Jeanne Baron’s blog, Ethical Guidance in Focus, compares the two, including highlights of what’s new from previous guidance documents and a table summarizing the implications.

- AVAC’s August 5th webinar, New Ethical Guidelines for HIV prevention trials in people: What’s changed and Why Does it Matter?, takes another step in explaining these updated essential documents provide context for their use. Hear advocates and bioethicists discuss the role of PrEP, community engagement, equity and more in future trial design.

- This factsheet outlines different trial designs under discussion, provides links to background material, and offers details on three trials being designed to test next-generation PrEP: monthly oral PrEP with islatravir from Merck; a new form of daily oral PrEP with F/TAF from Gilead; and six-monthly injectable PrEP with lenacapavir from Gilead.

From IAS 2021

If you are catching up on the 11th annual IAS Conference on HIV Science, AVAC has the resources you need.

- IAS 2021: Our Take and Updates rounds up the latest on the prevention pipeline, offers conference highlights on the intersection of COVID-19 and HIV, dives into new findings on PrEP and resistance, looks at how differentiated service delivery (DSD) has advanced and more.

- Research Literacy Zone Roundup offers links to sessions where researchers and advocates discuss critical questions for the field, including rollout of the Dapivirine Vaginal Ring, the status of vaccine and cure research, new approaches to address the social determinants of health, vaccine hesitancy and more.

The State of the Field for Rectal Microbicides

AIDS Foundation Chicago (AFC) and AVAC teamed up to host a webinar, Butt Stuff – All Gender HIV Prevention for Backdoor Action.

- The recorded session (access passcode: $v62dCvi) features the presentations on the status of research and development for options that focus on the rectum, where HIV infection often occurs.

- The slide presentations are also available as a PDF.

- And you won’t want to miss the accompanying playlist, from DJ Taylor Waits.

The State of the Field for Multi-Purpose Technology

Next up in the AFC and AVAC webinar series, Can Fantasies Become Realities? The Quest for Multi-purpose Prevention Products, is on Wednesday, October 13 10am–12pm EDT. Researcher Dr. Sharon Hillier and others will discuss the need for products that not only prevent HIV but are contraceptive as well, or prevent other STIs—or all the above. This webinar will also feature performers and a live DJ. Register today!

Enhancing HIV Prevention with Injectable Preexposure Prophylaxis

Quarraisha Abdool Karim, Ph.D. writes about the results of HPTN 083 and the implications of long-acting injectable of PrEP with cabotegravir in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Cabotegravir for HIV Prevention in Cisgender Men and Transgender Women

The results of HPTN 083, a trial evaluating the safety and efficacy of the injectable drug cabotegravir (CAB LA), for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in HIV-uninfected cisgender men and transgender women who have sex with men (MSM and TGW), in the New England Journal of Medicine.

IAS 2021: Our take and updates

COVID-19 may have forced some limiting factors onto the 11th IAS Conference on HIV Science—the conference was primarily online; the attendance was lower; and we couldn’t interact with our colleagues face-to-face—but moving in and out of virtual sessions, something transformative was in the air. The intersection of the responses to COVID-19 and HIV and the glaring disparities in health made ever more undeniable by COVID-19, are giving new meaning and momentum to changes advocates have been pressing for years, even decades. Where to begin…

- DSD: The time is now

- The latest on the prevention pipeline

- And vaccines?

- COVID-19 and HIV

- PrEP and resistance

- Calls for people-centered solutions

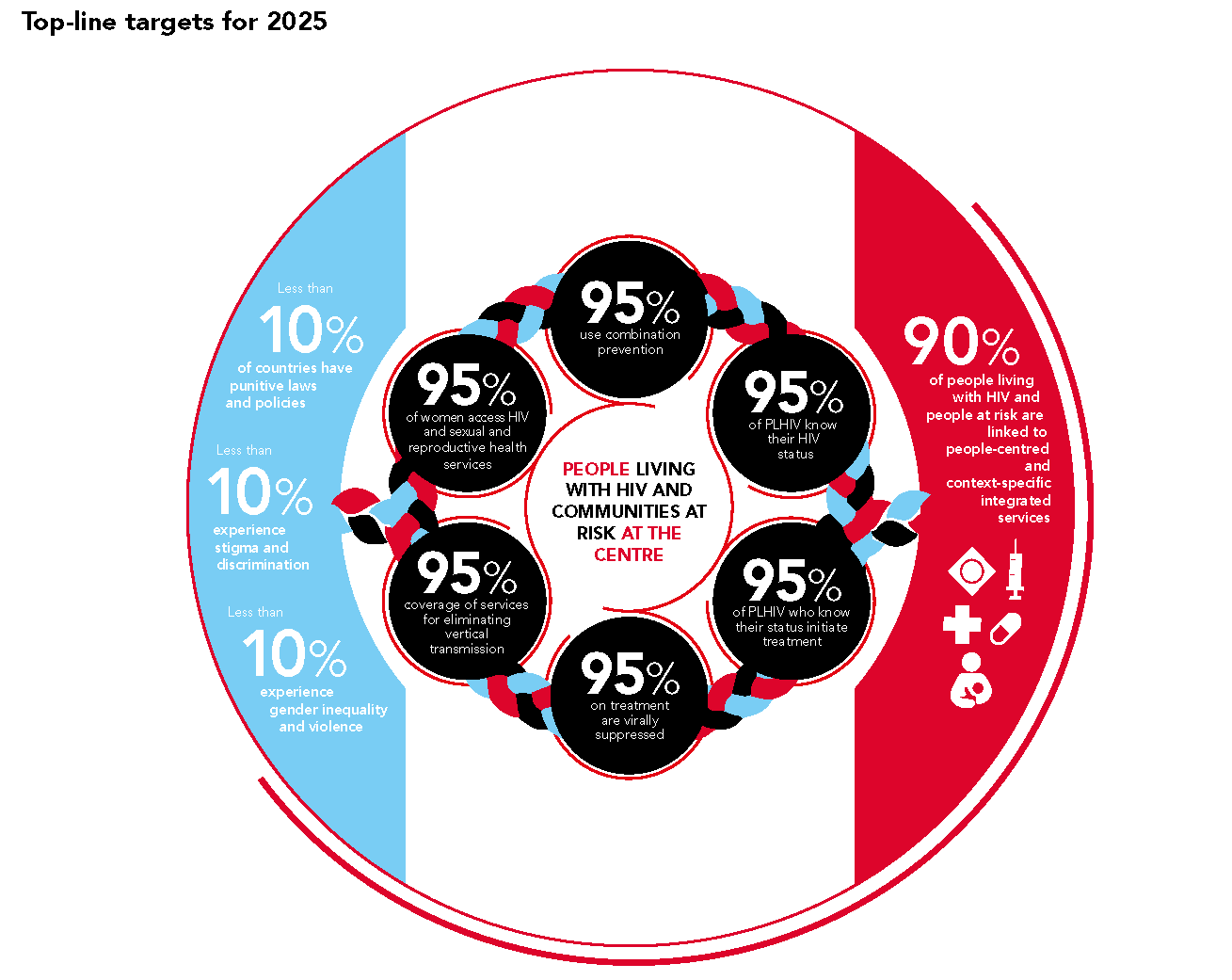

- New targets, old problems

DSD: The time is now

Differentiated service delivery (DSD) accelerated by orders of magnitude—telephone counseling, dispensing multi-month supplies of drugs, home delivery, community-based refills, and other innovation staved off hundreds of thousands of predicted HIV deaths, which were expected if people couldn’t get to the pharmacy or the clinic for treatment during COVID-19 lockdowns.

Multiple conference sessions referred to numerous initiatives where DSD scaled up rapidly, and with success. A few examples: An initiative from the CQUIN network coordinated among 21 different countries to share resources and lessons on DSD. PEPFAR’s Catherine Godfrey reported from a review of 52 countries that found 30 of them had scaled up and expanded eligibility for multi-month dispensing for treatment, with a 79 percent increase in the total number of people receiving a six-month supply of drugs. A different review from seven PEPFAR-supported countries, showed overall treatment interruption did not increase. And a UNAIDS analysis showed global trends in ART initiation continued despite the lockdown. Crucial to these successes, said Godfrey, were community health workers and community-based drug distribution.

These lessons from antiretroviral treatment have been applied in prevention as well. The session, Paving the road for new PrEP products: The promise of differentiated, simplified, and decentralized delivery to maximize the potential of new products, expanded the discussion on the need for innovations in PrEP delivery. Panelists at the satellite session, convened by AVAC, IAS and PATH, noted delivery must evolve as new products move through the pipeline, or years will be wasted with low uptake. Simplifying and Improving PrEP Delivery is one of four issue briefs just published by the Prevention Market Manager project and launched at the satellite, along with Reframing Risk in the Context of PrEP, Generating and Sustaining Demand for PrEP, and Next Generation M&E for Next-Generation PrEP. All echo core principles embedded in DSD: center the development of programs, policies and products in the leadership and knowledge of those who need prevention most.

This movement to DSD holds tremendous potential for prevention just as the field is poised to add powerful new prevention options to the tool kit. Data on next-generation options were also presented at IAS.

The latest on the prevention pipeline

Days before IAS began, The HealthTimes reported Zimbabwe’s approval of the monthly Dapivirine Vaginal Ring (DVR), which would be the first country to do so. Data presented at IAS on ring use from the REACH study underscore what can be achieved by tailoring the design of products and programs. REACH is a study looking at safety and adherence of oral PrEP and the ring in young women ages 16-21. Data from the study showed a marked increase in adherence to both the ring and oral PrEP among adolescent girls compared to previous studies. The key factor in the uptick? Intensive, individualized support that allowed participants to select from a menu that included text messages, weekly check-ins by phone, “peer-buddy” and adherence support groups. These findings build on evidence from other studies, including the POWER study, that adolescents greatly benefit from intensive adherence support. REACH data on preferences between the ring and oral PrEP are forthcoming.

A ring-focused session—Intravaginal options: Today and in the future—covered a lot of ground, from early-stage research on multipurpose rings for prevention, to work the World Health Organization (WHO) is doing to help facilitate the introduction of the Dapivirine Vaginal Ring. The WHO already recommends the ring and its Coordinator of Treatment and Care in the Department of HIV/AIDS, Meg Doherty, said the WHO plans to develop tools and guidance to assist countries to fit this new tool into their context, work on the supply chain, generate demand and more. These tools and guidance are expected by early 2022.

On the research front, Andrea Thurman (CONRAD) presented data from Phase I studies of a ring loaded with levonorgestrel (LNG) and tenofovir (TFV) and showed it is safe, acceptable and met benchmarks for drug levels in the body. Further research is warranted. Another presentation in that session came from Sharon Hillier (UPMC Magee-Womens Hospital), who presented highlights from the pipeline of intravaginal ring research including a three-month Dapivirine Ring and a novel MPT ring that’s both non-hormonal and includes a non-ARV-based antiviral.

A satellite session, Bringing the Dual Prevention Pill to Market: Opportunities for HIV and Pregnancy Prevention and Implications for Future Multipurpose Prevention Technologies (MPTs), reviewed the status of the Dual Prevention Pill, which could be available as early as 2024. If approved, it would be the first MPT to go to market since male and female condoms. This novel strategy provides unprecedented opportunities to integrate sexual and reproductive health (SRH) with HIV services, but major challenges must be met. The field of women’s health and family planning, policy makers and all stakeholders will need to understand why and how HIV prevention is their priority too, and how the DPP fits in the context of community health. Early, frequent and comprehensive consultations across both fields can and must serve as a model for breaking down these silos.

In a late-breaker session, Sharon Hiller presented data from the Phase 2a study of monthly oral islatravir, building on data presented earlier this year at HIVR4P. Hillier’s presentation at IAS 2021 showed this strategy met—and exceeded—key benchmarks for drug levels in the body that researchers think will be needed for it to be effective. The week-24 data also showed that it’s safe and well-tolerated. Efficacy data on this new prevention option will come from two large-scale efficacy trials (IMPOWER-22 and IMPOWER-24), results of which are expected in 2024. Islatravir is also being studied for long-term use via an implant.

And vaccines?

With a robust non-vaccine prevention pipeline, some of the vaccine session titles seemed to hint at a field wondering about its place: Will there be a next generation HIV vaccine if current ones fail?; An HIV vaccine: who needs it?; and HIV vaccines and immunotherapy: Quo vadis? (Latin for “Where are you going?”) The answer to that question is that HIV vaccine research is moving forward. Discussions at these sessions pointed to intensifying global interest in vaccine research and implementation, with COVID on everyone’s mind—and much of the success in COVID vaccines owed to the legacy of research in HIV. HIV vaccine research is moving forward with diverse approaches, and efficacy data from the two ongoing large-scale trials of Janssen’s Adeno 26-based vaccine are expected within the next two years. The AMP trials, and their implications for vaccine and antibody research, were also part of the discussion and are discussed in more detail in our recent document, Understanding Results of the AMP Trials.

But this momentum can’t be taken for granted. As Lynn Morris, from the University of the Witwatersrand and a leading antibody researcher, said in her plenary, it’s important now to galvanize political will, support increased investment and industry involvement in HIV vaccine development, run more parallel trials and take more risk.

And no matter the challenges of vaccine science, once available people will need to take it. AVAC’s Daisy Ouya reminded attendees at a UNAIDS/HIV Vaccine Enterprise satellite session that early and consistent community engagement is essential. If the field is going to reach coverage targets, community mistrust can’t be a barrier.

COVID-19 and HIV

A WHO report found HIV is a risk factor for severe or critical COVID-19. The WHO Global Clinical Platform for COVID-19 drew data from 24 countries and more than 15,000 people. This report offers another picture on HIV and COVID from the largest pool of data to date compared to other smaller studies that did not find a link, including one from the US, also presented at IAS 2021. The results have reinforced the need to ensure people living with HIV are listed as priority populations to receive COVID vaccines across the globe. This must happen in the context of massive scale-up to produce and distribute vaccines and close the gap in vaccination between the global north and south.

PrEP and resistance

The GEMS project monitored for the development of drug resistance among PrEP-takers. The project analyzed samples from 104,000 people from PrEP programs in Eswatini, Kenya, South Africa and Zimbabwe. There were 229 documented seroconversions overall and 118 were sequenced (some participants didn’t provide samples and some samples had low viral load and couldn’t be sequenced). Of those 118, 23 percent had HIV with a PrEP-associated mutation for drug resistance. Urvi Parikh, Senior Project Advisor of GEMS, presented the data and put the findings in context: the number of reported infections while on PrEP was very small, and an even smaller number had resistant mutations.

Based on the GEMS data, the most common mutation, M184V/I, is not expected to undermine the efficacy of one of the most important treatments across Africa, dolutegravir-based regimens. It will be important to monitor where these mutations will affect future treatment. It will also be vital to carefully screen for HIV among people who want PrEP in order to catch early infections that could lead to resistance. For additional background, our colleague Gus Cairns did a terrific summary of these findings as part of the NAM/AIDSMAP reports throughout the conference.

Calls for people-centered solutions

IAS 2021 heard an emphasis on the importance of community-led, client-controlled empowerment and leadership, which starts at the beginning of the research process, framing the questions that must be answered and how to answer them.

No Data No More: Manifesto to Align HIV Prevention Research with Trans and Gender Diverse Realities launched during IAS 2021. Developed by trans and gender-diverse (TGD) advocates from South Africa, Europe and the United States, with support and solidarity from AVAC, the manifesto demands an HIV prevention research agenda based on the priorities of TGD communities, with those communities driving decisions throughout the process.

Among the demands: provide gender-affirming hormone treatment (GAHT) across the continuum of HIV research, prevention and care; address the barriers that limit access to research and prevention for TGD people; recruit TGD researchers and other experts to design and implement solutions at all phases of the response.

At a session, What is missing in the HIV response?: Strengthening HIV programmes for trans populations in the Global South, presenters decried the absence of data on trans health outcomes even as TGD people face high risk of HIV. See US CDC statistics that show 1 in 7 (14 percent) transgender women in the United States have HIV and an estimated 3 percent of transgender men have HIV, with even less data available for non-binary individuals.

Liberty Matthyse of Gender Dynamix in South Africa said “trans and gender-diverse healthcare is greatly understudied,” fundamentally undermining the effort to end the epidemic. “We need to prioritize community-led participatory research, plug into existing community-led movements, co-create context-specific methodology to reach missing and undocumented cases. And we need to decentralize access to hormonal care and make it part of a package of HIV services. Every person should have the right to gender self-determination.”

Rena Janamnuaysook’s presentation at this session provided a model. At Thailand’s Tangerine Clinic, members of the trans community identified priority health needs, co-designed a program of services, and received training to deliver qualified care. About 4,000 community members rely on the clinic, which offers hormone services and other gender-affirming care as an anchor to generate demand for other health services including HIV testing, prevention and treatment. Nearly all (94 percent) of the 10 percent who have tested positive have initiated ART, nearly all of them (97 percent) are virally suppressed, and 18 percent of those who have tested negative initiated PrEP. “Key populations-led services increased access to testing, simplified services, and promoted a sustainable HIV response,” said Rena.

New targets old problems

These stories from IAS 2021 put the past year in perspective. The science that was needed to respond to both SARS-CoV2 and HIV has seen significant advances and must continue. The innovation to deliver treatment and prevention has also seen unprecedented effort, and must accelerate and expand. But policy and political will has failed to close gaping inequities that mean, among other things, the 3.3 billion doses of COVID vaccine delivered to date are concentrated in a few wealthy countries, that lockdown drove up reports of rape in Uganda by 24 percent while the use of PEP dropped by 17 percent, that 150 million people will fall into extreme poverty this year, that COVID remains a threat to global health everywhere.

The new UNAIDS targets, the so called “10’s” aimed at social factors that drive epidemics (punitive laws and policies, stigma, discrimination and gender-based violence) should galvanize action from every quarter. Approved by the UN’s High Level Meeting on HIV in June, these new targets must be used to build on the sweeping changes underway in 2020, to dismantle structural barriers and to embrace new evidence-based models that will make prevention a reality everywhere it’s needed.

Understanding the AMP Results and So Much More

We’re delighted to share our new publication Understanding Results of the AMP Trials. The first results of these landmark trials were announced in early 2021, but their implications will be echoing for years to come. This guide provides a foundation for advocates.

The AMP trials evaluated the ability of a broadly neutralizing antibody (bNAb), called VRC01, to protect against HIV. The trials showed that VRC01 did not reduce the overall risk of acquiring HIV. However, VRC01 protected some individuals from infection by HIV viruses that were particularly vulnerable or “sensitive” to the antibody. Together these results mean AMP will inform future bNAb and vaccine studies. Read Understanding Results to learn more; listen to our Px Pulse podcast to dive into the AMP trials; and check out AVACer Daisy Ouya’s commentary on the AMP trials in the latest issue of IAVI’s Voices: Community Perspectives on Clinical Research.

Also, in case you missed it, we’re highlighting a few other important resources to inform prevention advocacy:

- More on Antibodies: IAVI and Wellcome recorded this webinar, Enhancing regulatory and policy frameworks for monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) in Africa: lessons learned from vaccines.

- All Things PrEP: The PrEP Learning Network hosted a webinar, Reframing PrEP Continuation: Highlights from the PMM-Jhpiego-USAID Think Tank on Prevention Effective Use Of PrEP.

- Put a Ring on It: The latest issue of the quarterly PROMISE-CHOICE Dapivirine Ring Newsletter features updates on advances of the Dapivirine Vaginal Ring. Find news from researchers, civil society, country implementers and invitations for workshops and other events.

- PEPFAR Needs a Leader: Devex recently published a commentary, US leadership matters in fighting AIDS, co-authored by AVAC’s Mitchell Warren and Emory University’s Carlos del Rio on the imperative for US President Joe Biden to end the delay in appointing PEPFAR’s next leader.

- What’s Your Pleasure: The HIV prevention research pipeline, including a wide array of molecules and modalities (backed up by a smokin’ DJ), was the subject of this webinar, What’s Your Pleasure? Expanding Your Choices on the HIV Prevention Buffet. Access Code is required: iz5TqS2*

PrEP “Cycling”: The dance of oral PrEP

The landscape for PrEP is in the midst of transformation, with opportunities to understand and improve HIV prevention. With increasing numbers taking oral PrEP and new products on the horizon, such as the Dapivirine Vaginal Ring and long-acting cabotegravir, the world must get rollout right. There are vital lessons to learn from how people use oral PrEP and critical questions to answer. AVACer Jeanne Baron’s blog, PrEP “Cycling”: The dance of oral PrEP explores one key lesson from today’s PrEP-users that could mean a new definition of success with PrEP.

And be sure to check two recent reports from AVAC’s Prevention Market Manager (PMM) project and Jhpiego, Evaluating, Scaling up and Enhancing Strategies for Supporting PrEP Continuation and Effective Use and Defining and Measuring the Effective Use of PrEP which offer key recommendations for this evolving field.

PrEP “Cycling”: The dance of oral PrEP

By Jeanne Baron

Oral PrEP, a daily pill first approved by the FDA in 2012, has changed a lot of things for the better for Josephine Aseme. At the start of 2021, more than a million people had at least started PrEP at some point since 2016—it’s movement in the right direction, but still shockingly short of the global target to reach at least three million people in that time-frame. Still there’s no question, it’s an essential HIV prevention option for Josephine and for many of the 12,000 women in the organization she founded in 2015 for women at risk, the Nigeria-based Greater Women Initiative for Health and Rights.

As a leader for sex workers’ rights, an advocate for poor and vulnerable woman, an AVAC Fellow and a sex worker herself, Josephine says she began taking PrEP in 2017 and quickly understood this pill would change her life. “PrEP really made a big impact for me. Clients cannot be trusted; they will deliberately misuse condoms, and I may not notice or be able to stop them. I was always scared of HIV. PrEP came along and empowered me to know that I can stay [HIV] negative.” So why is it that many PrEP users, including Josephine, sometimes “cycle off” PrEP, at least for a time? Understanding this question is imperative.

PrEP only works if you take it. For years, public health messaging, programs, services and data collection have attempted to reflect this fact of biology. A person has to have a certain level of drug in their body to be protected. This means that missed doses and missed appointments for refills, days and weeks not taking the preventive medication, represent a challenge, if not a serious problem. This in turn has led many to consider the discontinuation of PrEP as a potential failure; of programs and policies, of leadership and decision-makers, or even of users.

But the conversation is changing and stories from PrEP champions like Josephine, as well as data from studies, are leading the way. Josephine has counseled countless women on the potential benefits, risks and use of PrEP, and she herself has dropped her daily pill for periods of time only to later pick it up again.

A growing body of research about what’s behind this “cycling” points to a cross current of pressures. Many have been documented and are clearly barriers to PrEP use: side effects, stock-outs, fear of disclosure to partners and family, stigma and access issues, among others. But some people consciously choose to stop taking their pills, keen to give their bodies a rest from daily medication as they enter a period of their lives when HIV’s shadow is not so long.

While programs must have the resources to deliver PrEP to everyone who can benefit from it, a conversation with Josephine Aseme suggests there’s much to learn and understand about these patterns of use, and how policies and programs can support people to take PrEP when they need it.

Josephine has stopped taking her daily pill several times in the last five years. Once when traveling, she forgot her pills and found herself in a region where there was no access to PrEP. “I was away for a week and I reached out to other KPs [key populations eligible for PrEP] to see if I could get pills. It was sad. There was no PrEP there.”

At least twice she confronted stockouts after traveling hours to her regular “One-Stop-Shop” that offers stigma-free services for key populations. The month she visited her family she wasn’t working and dropped the pill while there. And during the terrifying month of March 2020, when COVID-19 shut down everything, she stopped taking PrEP.

And then there was the time she just got fed up. “I’d been on PrEP a long time. I was saying to myself ‘I’m tired.’ Some part of me was thinking, ‘enough of this medication has been in my system. I’m going off for two or three months.’ But at the same time, I was still doing sex work and I was still scared of HIV.”

Eventually that anxiety drove Josephine back to PrEP and she has not cycled off since May 2020. She says her experience with going on and off PrEP is typical. One of her own staff, another PrEP champion and a sex worker, went off PrEP for a time. “When I learned about it and asked her why, it was clear she understood the consequences. But I wasn’t surprised because I have gone through the same stage. She was just tired of taking a pill. She’s back on it now.” And why did she go back on it? Josephine offers insight into this.

In one of her programs at Greater Women Initiative for Health and Rights, Josephine offers support to sex workers at hot spots where they meet clients. Her conversations from this outreach put a spotlight on the struggle to stay HIV negative, and the pressures, fears and opportunities that spur a return to PrEP.

Josephine goes to the hot spots to share prevention messages, and remind people that they can stay negative. “I’ll see people I have helped to get PrEP, or provided referrals to PrEP, and they’ll tell me ‘sorry, my pill finished months ago, but now I feel like I need to go back to the pill’. Josephine says brothel owners will send them packing if they become positive. Most of the brothel owners encourage regular and mandatory HIV testing. “That fear will bring others back on track with PrEP. Maybe someone they know has just become positive. Sometimes my phone will ring with someone saying ‘I just remembered to call you today, please where can I get PrEP. I am in a new location now, where I can find it.’ We see this a lot in our program.”

The SEARCH study, conducted among the population of 16 communities in rural Kenya and Uganda since 2013, has provided telling data on these patterns. Still ongoing, SEARCH studied interventions to bring down the incidence of HIV, including rapid access to PrEP with counseling, and flexible options for follow-up, among other things. Among the key findings: 83 percent of study participants stopped PrEP at least once (half of them later restarted). Among those who initiated PrEP, incidence went down 74 percent (compared to control groups that were not offered this enriched program for PrEP) even though self-reported adherence among the whole cohort was never better than 42 percent and declined to 27 percent by week 60. The explanation may be that those who self-reported being at risk showed much higher adherence, never lower than 70 percent.

These data along with data from the US, the UK and Australia, among other high-income settings, suggest “coverage”—getting enough PrEP to the people who need it—can result in lower incidence across a population of PrEP users, even if many people are cycling on and off. It’s a picture that demands more nuance in how the field defines using PrEP effectively.

Two recent reports from AVAC’s Prevention Market Manager (PMM) project and Jhpiego, Evaluating, Scaling up and Enhancing Strategies for Supporting PrEP Continuation and Effective Use and Defining and Measuring the Effective Use of PrEP offer key recommendations to address these complex issues: the field should develop new definitions and metrics for effective PrEP use that anticipate that people will cycle on and off; a new focus on the impact of all PrEP products on reducing HIV incidence is needed; and more research must be done to understand the range of reasons people discontinue and return to PrEP.

Supporting people during seasons of risk to stay on PrEP will be relevant to the next generation of prevention products, including the Dapivirine Vaginal Ring (DVR) and injectable cabotegravir (CAB-LA), both approved by regulatory bodies and moving toward introduction, as well as the PrEP strategies still being tested, such as the islatravir monthly pill and injectable lenacapavir.

Even though these methods are longer-acting than daily oral PrEP, they each come with challenges. People will also start and stop or switch products. Exactly why and when, and how they find their way back to prevention must be better understood. Reaching women in remote villages in languages they understand must be part of the plan. And all this knowledge must be applied to programs and policies that should soon be offering an increasing number of options. Will those options be integrated into services that result in meaningful choices for Josephine Aseme and the women she works with? Josephine says she certainly hopes so, because sticking with daily oral PrEP has been hard, a life-saving yoke that sits heavily.

As a panelist at a recent prevention conference Josephine said a lot of the information wasn’t new, but she got excited when someone said PrEP is not a lifetime pill. “I really liked hearing this; the idea that I don’t have to be on PrEP forever. I am grateful for PrEP having my back all these years, for protecting me. But I am not happy taking it every day. I want to be able to choose other methods to protect myself. Every time I counsel someone who is initiating PrEP they ask me ‘how long do I have to be on it’ and it’s so good to say, ‘it’s not a lifetime pill. When you are still at risk, take the pill. When the risk stops, so does the pill.’”

###

Other publications coming from the PMM explore related topics in-depth: Lessons from Oral PrEP Programs and Their Implications for Next Generation Prevention, to be published shortly, draws lessons from the introduction of PrEP in terms of demand creation, the design of delivery, assessing impact and more. And a series of highly-focused briefs, also to be published in the weeks to come, will dive into key technical recommendations. Watch out for these!

40 years of HIV/AIDS, and 18 months of COVID: Resources and Perspectives

It’s 18 months and counting since COVID-19 hit the world, and it’s 40 years this week since the first cases of HIV appeared in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report of the CDC. Both epidemics have deeply scarred humankind, and neither can be vanquished without prevention. That message is vital to remember as the UN High Level Meeting (HLM) on AIDS begins next week—20 years since the first UN General Assembly Special Session on HIV/AIDS that led to the establishment of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria.

At AVAC.org we have new resources to support your advocacy and get you the latest information on the prevention pipelines for both HIV and COVID-19—and some recommended reading, too, from some friends and colleagues:

- Chris Beyrer just published this perspective in the Lancet: A pandemic anniversary: 40 years of HIV/AIDS

- Emily Bass and Ethan Guillén contributed their point of view in Foreign Policy: Tackling Pandemics Means Relearning the Lessons of Fighting HIV

We hope you’ll scroll down for a roundup of recently updated materials. And we hope you’ll join a side meeting at the HLM, No Prevention, No End: The importance of leadership for HIV prevention—How decisions can turn an epidemic. Register to support the urgent need for leadership to reach the 2030 UN targets. And to see the larger conversation of the HLM, and AVAC’s take, on Twitter, follow #HLM2021AIDS.

The HIV Prevention Pipeline

- AVAC’s classic infographic, The Future of ARV-Based Prevention and More, has a fresh update. It offers a look at the range of non-vaccine technology moving from pre-clinical through phase IV trials.

- HIV Vaccine Awareness Day on May 18th brought a slew of resources for vaccine advocacy. On AVAC’s dedicated page for HVAD 2021 you will find key messages, a PowerPoint for basic vaccine science, podcasts, opinion pieces and more.

- You won’t want to miss the June 29th webinar, What’s Your Pleasure? Expanding Your Choices on the HIV Prevention Buffet. The talk will be both a scientific update on the research pipeline—with Dr. Linda-Gail Bekker from the Desmond Tutu Health Foundation, Dazon Dixon Diallo from SisterLove, and Rob Newells from the Black AIDS Institute—and a happenin’ gathering with spoken word artist Storie Deveraux and DJ set by DJ Triple D. Register here.

Updates On COVID Vaccines

- Check out the latest on the Cheat Sheet: COVID-19 Vaccine Pipeline. This snapshot offers advocates a view of the funders, platforms and progress through the clinical research process.

- The COVID-19 Vaccine Cheat Sheet: Access Edition features updates on how vaccines compare on key characteristics such as cost, dosing, efficacy and more.

HIV Vaccines: The basics

This introductory PowerPoint slide set reviews basic concepts, and provides an overview of research status and recent developments.

New Resources on AVAC.org and PrEPWatch

In this round-up of new AVAC resources you’ll find a wide range of new resources:

Understanding the Latest in HIV Prevention Research

HIV Vaccine Awareness Day is just around the corner—May 18th! In preparation, AVAC hosted a webinar, HIV Vaccines in the Midst of COVID, on Thursday, May 13.

An Advocates’ Primer on Long-Acting Injectable Cabotegravir for PrEP: In 2020, two large-scale efficacy trials, HPTN 083 & 084, found that a long-acting injectable form of cabotegravir as PrEP provided high levels of protection among people at risk of HIV. That’s truly exciting. There’s also a lot to learn and understand about next steps. What do the trial results explain, what still needs to be explored, and what do advocates think needs to happen next? Check out our primer for what’s known and what’s next for this emerging biomedical HIV prevention strategy.

A webinar: Long-Acting Injectable Cabotegravir for PrEP – Understanding the results and key areas for advocacy: AVAC’s May 3rd webinar on CAB-LA featured the researchers who led the studies on long-acting injectable PrEP, and advocates who are defining key issues for the introduction of CAB-LA.

Dive into the AMP Trials: In this episode of Px Pulse, AVACers Jeanne Baron and Daisy Ouya talk to leading bNAb researcher, IAVI’s Devin Sok; veteran HIV research advocate Mark Hubbard who served on AMP’s protocol team; and a senior member of the HVTN’s community engagement team, a chief explainer of the AMP trails, Gail Broder. Together they explore why these findings point to the need for combination antibodies, the need for a better understanding of the types of HIV that are circulating in a community, the complicated implications of a key lab test, the TZM-bl assay, and more.

Developments in the HIV Prevention Pipeline: PrEP, vaccines and more: Created by AVAC, EATG, PrEP in Europe, and PrEPster, this slide deck and recorded webinar offers community educators and advocates a concise summary of existing and future PrEP products, and a community-level perspective on strategic advocacy for PrEP access and uptake.

Watchdogging PEPFAR

PEPFAR Watch is a new online resource from a collaboration working to hold PEPFAR accountable to communities. The website features reports, news, and resources to support community-led monitoring, a core initiative for accountability in PEPFAR programs. You can also sign up to become members and gain access to webinars, PEPFAR quarterly data and more. The collaboration includes Health GAP, AVAC, TAG, the O’Neill Institute, MPact, the PLUS Coalition, amfAR, and CHANGE. It should be a one stop shop for all the information you need to monitor and influence PEPFAR Country Operational Plans. Find other supportive resources on AVAC’s page: Advocate for Access to High-Impact Prevention.

A Spotlight on Equity and Ethics

Make Your Voice Heard: Towards advancing racial equity & diversity in biomedical research: In response to a call from the NIH for proposals to advance racial equity, diversity, and inclusion within all facets of the biomedical research workforce, and expand research to eliminate or lessen health disparities and inequities, AVAC’s John Meade authored a blog on the major recommendations offered to the NIH from a coalition of 25 HIV research advocate organization.

How can research ethics committees help to strengthen stakeholder engagement in health research in South Africa? An evaluation of REC documents: This article, co-authored by our CASPR partners at South Africa’s HIV AIDS Vaccines Ethics Group (HAVEG) and AVAC’s Jess Salzwedel, and published in the South African Journal of Bioethics and Law, recommends research ethics committees (RECs) step up the focus on stakeholder engagement. Researchers working with REC’s should plan for robust stakeholder engagement and REC documentation should be harmonized to reflect this priority.

Advocacy for Vaccine Access

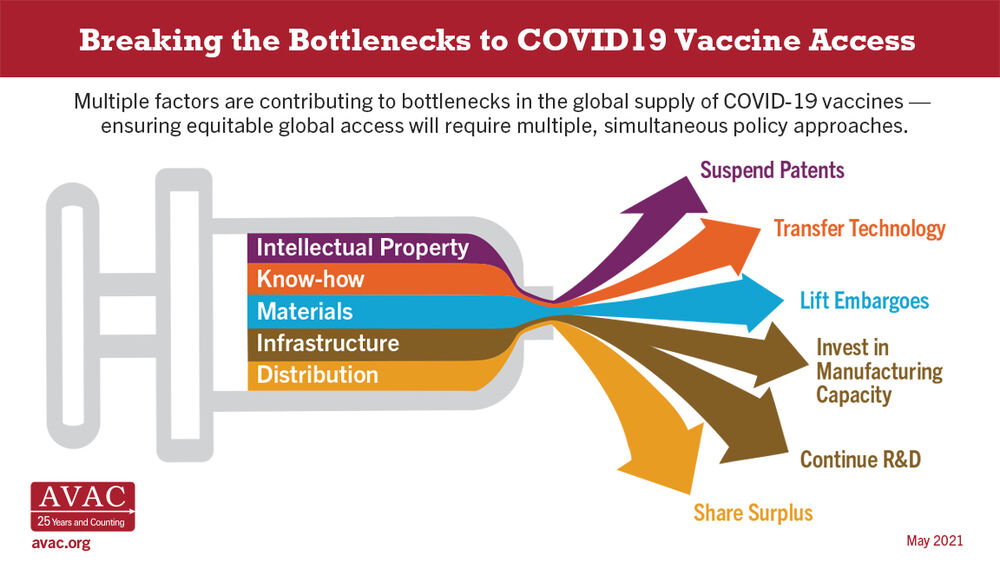

Breaking the Bottlenecks to COVID-19 Vaccine Access: Ensuring global access to COVID vaccines—and any health commodity—requires a multi-pronged effort to get the right policies in place. This new infographic identifies the multiple factors that contribute to bottlenecks in the global supply of #COVID19 vaccines and how to address them.

We hope these resources, which cut across issues facing the field, will empower your advocacy where change is both crucial and possible.