June 21, 2024

Written by Namiganda Jael, a journalist in Kampala, Uganda. She is a health reporter, writer and anchor at Metro 90.8 FM. She is also media coordinator at Health Journalist Network Uganda and a member of Tobacco Harm Reduction Uganda and the Uganda Parliamentary Press Association.

When she felt a bruise on her private parts, Ramzay, a transgender woman and a sex worker who prefers to be identified by only one name for fear of persecution, rushed to the nearest health center for treatment.

While there, Ramzay asked the doctor for an ointment cream. The doctor loudly wondered if she was gay because the ointment cream was for gay people.

“I felt embarrassed and stigmatized by the rudeness of the doctor and her coworkers,” she said, adding that the doctor’s response was a negative attitude she’d repeatedly experienced in other public hospitals whenever she visited to seek health services, including Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) prevention.

When Ramzay tested HIV negative at the beginning of 2023, she decided to visit a local group, Justice and Economic Empowerment for Women and Girls Organization (JWEEG), for HIV preventive products, such as condoms, lubricants, Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), and post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP).

However, when the anti-homosexuality bill was signed into law by President Yoweri Museveni in May 2023, she became worried that access to HIV preventive treatment would be hampered. She was right.

PrEP and PEP are treatments for people at risk of HIV exposure. PEP is more commonly used and is given to people who have been raped and to medical professionals exposed to HIV while working. It’s only given to people who have tested HIV-negative.

JEEWG was founded in 2015 by Waseni Harriet, also known by her trade name Cindy. Her focus was to bring HIV preventive methods such as condoms to Kasensero village, where she saw her fellow sex workers washing and sharing condoms.

It started with 25 members, but today, the organization has over 1,000 members who seek a wide range of services, including sexual and reproductive health, Waseni said.

To achieve her goal, Waseni looked for health service providers she could partner with to help bring HIV prevention and treatment measures to her community, including men who have sex with men and transsexual women.

But together with her partners, she did not give up. “So, we try to follow up on cases, especially those in the LGBT community affected by the law. At MARPI, we get all kinds of HIV medication; we collect ARVs for those who cannot pick it up from the facility because of fear or stigma,” she says, adding that for those who have relocated because of the law, HIV medication is taken to them or rendered to them in the nearest pick-up centers in the new areas.

In May 2023, Uganda passed a draconian and unconstitutional anti-homosexuality law. Sub-section two of Section Two of the Act states that a person who commits the offense of homosexuality is liable on conviction to life imprisonment.

In November 2023, human rights activists went to the constitutional court seeking nullification of the impugned law, arguing that it violated the human rights of homosexual people.

The decision came on April 3, 2024. Despite the court agreeing with the petitioners that some sections of the law infringed human rights as they were “…inconsistent with the right to health, privacy and freedom of religion”, in a ruling read by Deputy Chief Justice Richard Buteere, it upheld the law to the chagrin of many observers.

Article 27 of the Constitution states that no person shall be subjected to unlawful search of the body, home or other property or to unlawful entry of his or her premises. Article 24 on freedom from inhuman treatment states that a person shall not be subjected to any form of torture, cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment or held in slavery.

With the constitutional court upholding the anti-homosexuality law despite such provisions, the petitioners filed an appeal at the Supreme Court in April, says Nicholas Opio, a human rights lawyer and one of the petitioners.

Opio says he was disappointed in the court’s ruling. “Striking section of the right to privacy and right to health was an attempt to appease donors to the health sector,” he says, adding the ruling didn’t help with safeguarding the rights of the LGBT community, whose existence is criminalized.

Genesis, a gay man who prefers to be identified by his first name only for fear of stigma and harm, says, “…nullifying some sections of the law seems to slightly calm the pressure on the health of the LGBT+ community, but the law in its entirety is ridiculous”.

“When the court nullified sections that obliged a medical practitioner or any other person to report suspected acts of homosexuality to police, I felt some slight relief because I am at least not worried about being reported by a doctor to authorities after learning that I am gay. “At least the patient-doctor confidentiality has been reinstated,” says Genesis.

Sharaim Ismael has been a sex worker since 2020 at the age of 18. As a transgender woman, she was assigned a male identity at birth but identified as a female. She has been moving from one place to another as a security precaution for her safety since the passage of the anti-homosexual law, she intimates.

“Because of my sexual identity and work, I left home because most people were threatening me, especially after the passing of the bill (Anti-homosexuality bill), so I ran away to northern Buganda,” she says.

Sharaim gets lubricants and HIV testing kits at JEEWG, which she uses to test her partners as she neither takes PrEP nor uses condoms as an HIV preventive measure.

PrEP is HIV medication administered to prevent people from contracting HIV from unprotected sex by 99%. With the Injectable drug, the risk is reduced by 74%, according to the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

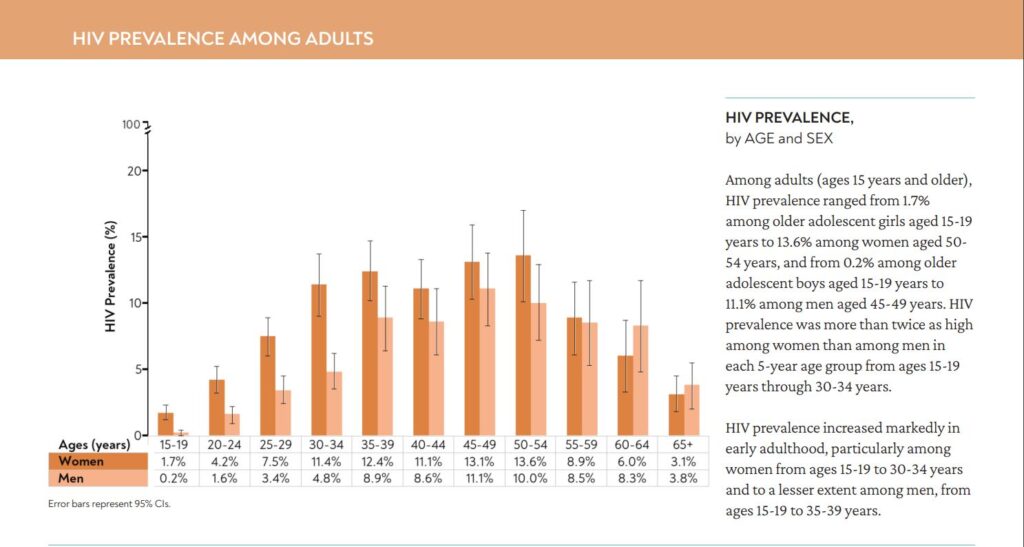

According to the World Health Organization, HIV prevalence among transgender women is estimated to be 28.4 in eastern and southern Africa. As of 2023, Uganda’s national HIV prevalence stood at 5.8%, according to the 2020-2021 Uganda Population HIV Impact Assessment.

In 2017, the Uganda Ministry of Health introduced PrEP and PEP into the country to fight against HIV infections. However, it has been mostly out of reach to gay people “because of the stigma in some health facilities where they don’t feel safe to seek health services,” Sharaim laments.

Ramzay and Sharaim are among the key populations (most at risk) in Uganda, a community of people at a higher risk of getting HIV.

Key populations in Uganda include sex workers, prisoners, men who have sex with men, truck drivers, fishermen, and bodaboda riders.

According to the Uganda Population-Based HIV Impact Assessment 2020-2021, the HIV rate in the key population is said to be at about 11%. This is almost twice the national adult prevalence rate of 5.8%.

Another organization helping LGBT+ people in Uganda access critical reproductive health services is the Children of the Sun Foundation (COSF). Thanks to donor funding, it operates a free clinic and shelter for LGBT+ people.

COSF Executive Director Henry Mukiibi says despite their constitutional protection, members of the LGBT+ community have been shamed and publicly castigated by health workers in some public and private health services.

“One LGBT+ patient came here suffering from a hemorrhage and told us how a doctor shouted at him to get out of his clinic, accusing him of being gay and promoting bad sexual behavior,” Mukiibi narrates.

Even with the stringent law, Mukiibi says the COSF clinic has a permanent nurse and an on-call doctor to attend to the patients.

For HIV prevention, the clinic provides testing kits, condoms, and lubricants to the LGBT QI community. However, for HIV treatments, they are referred to licensed health centers that safely provide HIV treatment services to the community.

But COSF also does home delivery of drugs to members of the community who don’t feel safe going to health facilities to pick up their drugs for fear of stigma, discrimination, and even violence, Mukiibi reassures. To get the deliveries, patients in need call COSF or send a colleague to submit a request for them. Sometimes, through phone calls and home visits, the Foundation also follows up with the patients who fail to turn up for their medicine.

Sam, who prefers to be identified by his first name for fear of victimization, had his ARVs delivered to him for several weeks by COSF because he feared getting out of the house for several weeks. After the passage of the bad law, he was violently attacked and abused by some members of the village due to his sexual orientation.

“The home delivery of my HIV treatment drugs came in handy. It helped me adhere to treatment until I gained the confidence to get out and also shift to a new home,” says Sam.

“For PEP and PrEP, we refer members of the community to organizations such as The Aids Support Organisation (TASO), a local NGO that has been supporting people living with HIV and also involved in the fight against HIV spread for over 30 years and REACH OUT, a Community Health initiative NGO providing HIV services working mainly with urban and rural poor communities in Uganda where they get such services,” Mukiibi says.

He adds that for members who don’t feel safe moving to public spaces, the clinic partners with such organizations, which are then invited to provide outreach services to the community gathered at the clinic.

Dr. Nelson Musoba, Director General of Uganda Aids Commission, a government agency that coordinates the response to the country’s HIV/AIDS epidemic, rightly says preventive measures should be accessible to everyone who thinks they are at risk of contracting HIV.

“Everyone in Uganda should have access to all available HIV treatment services in Uganda without any kind of discrimination regardless of who they are,” he says, adding that the anti-homosexuality law doesn’t stop anyone from accessing HIV treatment.

However, Mukiibi disagrees. “When we have laws that discriminate against LBGT people, you increase the risk of violence and discrimination against them. We have seen them being stigmatized and discriminated against in health service centers because of their sexuality. The law increases and feeds the homophobia attitude even in the health practitioners,” he says.

The Situation in Kenya

In neighboring Kenya, although the situation isn’t better than in other countries where anti-homosexuality laws have been passed, the LGBT+ people are better off when it comes to access to health services, says Ishmael Bahati, the executive director of Persons Marginalised and Aggrieved Kenya (PEMA) and co-chair of Gay Bisexual Men (GBSM), network in Kenya that brings together all gay, bisexual men organizations working on health.

“In Mombasa County, for example, we have 14 government facilities which we have already sensitized the service providers to offer not only friendly services but also specific services needed for the gay and GBSMs.”

“PEMA does not have a distribution chain; we only do referrals. However, with our position on the national level, like at the coast, we do referrals and advocacy on health, mainly ensuring that the public/ government facilities can offer services to LGBTQI persons,” he emphasizes.

With the constitutional court having upheld the draconian anti-homosexuality law, eyes now turn to the Supreme Court to appeal, where the petitioners have filed an appeal to overturn the lower court’s impugned decision.